So, I like to remind myself of how difficult it was to get around in the Old West days—the terrific and terrorizing journey to get to Southern California, and the near impossibility of traversing the transverse mountain ranges to get up north.

I find myself often following the path of now-phantom carriages.

Except recently, I had the chance to ride in a real stagecoach—in a kind of brief reenactment of the "Great Western Migration" that brought an adventurous lot along the Butterfield Overland Stage's

transcontinental mail route (the first of its kind, in fact).

That's what brought me to the Warner-Carrillo Ranch—located in the San Luis Rey River Watershed on the former Mexican land grant known as Rancho Valle de San José, whose land has been owned by the Vista Irrigation District of San Diego County since 1946.

Built in 1857, the Carrillo adobe and ranch house was the home of Don José Ramón Carrillo and Doña Vicenta Sepúlveda de Yorba de Carrillo (widowed from her first husband, Tomas Yorba), who married in 1847.

Starting in 1858, they operated a type of stage stop known as a "swing station"—where horses were changed—on Overland Mail Stage Line, at the fork in the road on the Southern Emigrant Trail (technically, the Gila River Emigrant Trail) between LA and San Diego.

At the time, Concord coaches—like the kind you still see paraded around by Wells Fargo, so named because they came out of Concord, New Hampshire—provided the ultimate in "luxurious land travel." Their wheels were fashioned of seasoned white oak with handmade spokes, both beautiful and more durable than the European-built stagecoaches that preceded them.

They'd make twice-a-week runs from St. Louis to San Francisco—and at just 5 to 12 mph, it would generally take 25 days and nights to complete the trip (though the record speed was 23 days and 23 hours).

Their primary purpose was to carry mail—but they could also carry 25 lbs. of luggage, two blankets, and a canteen.

That meant, for a $200 fare, you could book a spot in one of these "traveling hotels" as a passenger—and you'd sleep on it as it went, well, overland.

There were certain rules to follow, in order to make the trip as pleasant as possible for you—and your coach-mates. For example, if the horse team were to run away (which apparently happened often enough to warn you about it), you should hold tight and not jump ship.

And proper etiquette dictated that you not point out where murders have been committed, especially if there are women passengers present (Omaha Herald, circa 1877).

I would've sat perched up top—but I would've had to have held on with both hands, leaving no hand free for my camera. So instead, I rode inside sitting backwards (reportedly the better way to go) and welcomed the bandits who robbed us with offers of my heart and innocence.

By all reports, the journey was, quite simply, treacherous—replete with annoyances, discomfort, and plenty of hardship. Some travelers described it as "cruel and unusual punishment," with nine passengers crammed into three seats.

Our trip was raucous and rumbling—enough to give us whiplash—but so brief, it was just a teeny tiny taste of what it would've taken to get just from one stage stop to another.

What we rode, of course, was just one example—with a red-painted body and yellow-painted trim, like the rest of them were, though the coaches often varied otherwise in design.

We got dropped off by the original horse corral, which is still standing—barely. In fact, it's the only such barn—of hand-hewn timber—still standing in the county.

It's slated for future restoration, including the sliver of original adobe wall that remains.

The restored adobe residence (a state and national landmark) reflects an historical time in ranching history—including the raising of cattle, sheep, horses, pigs, goats, and more and the cultivation of grain crops.

You can see how canvas was stretched over rooms to make a ceiling (or "manta," which means "blanket" in Spanish).

Original wood ceiling beams (or vigas) were preserved in the restoration—including some that had been originally salvaged from other structure that had burned down.

Although it originally began as a two-room adobe, the verandas were eventually enclosed to create a total of eight rooms.

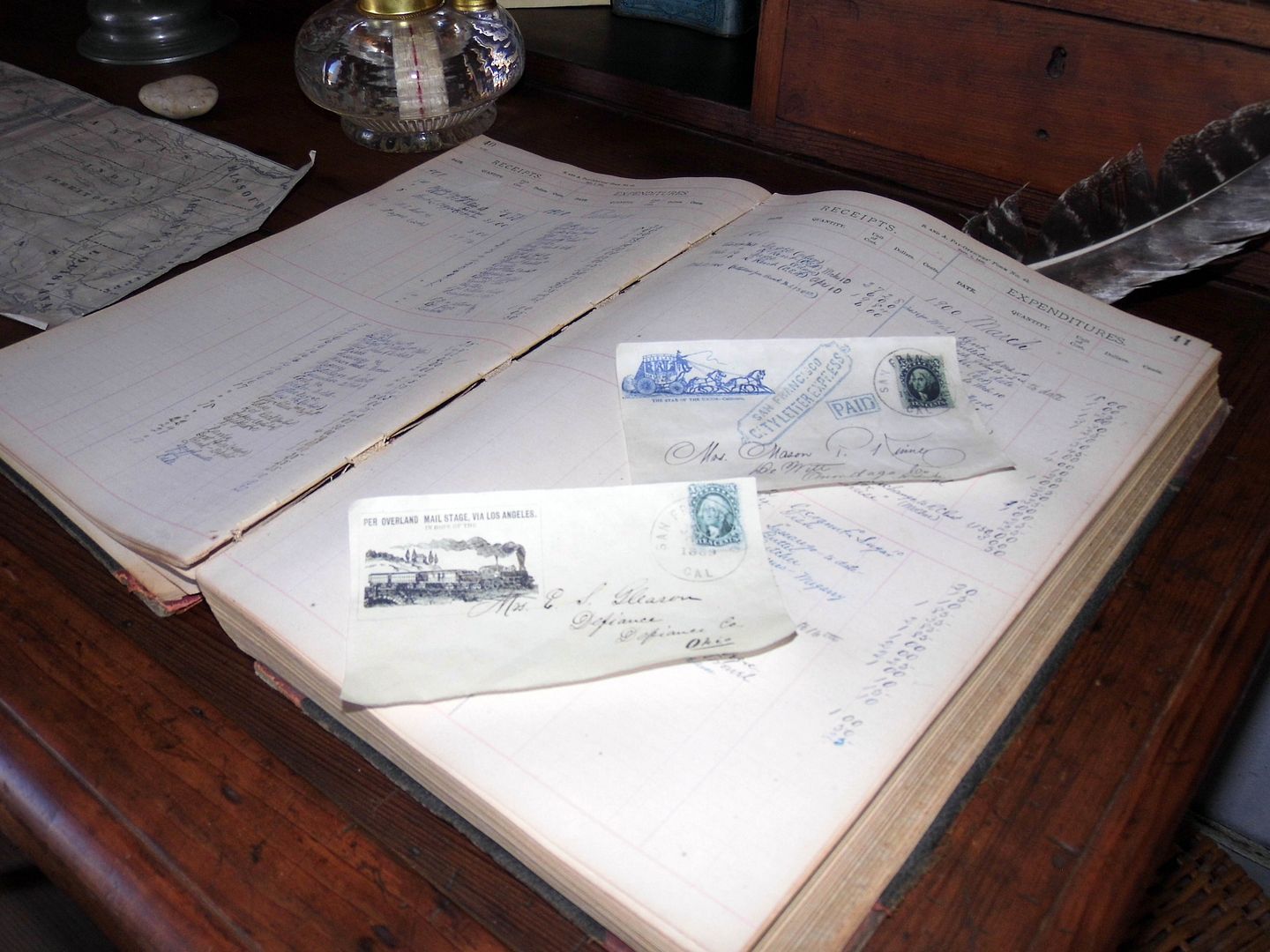

They needed the space for the business—namely, the trading post and post office that operated as part of the stage stop.

Ramón Carrillo became postmaster, despite the fact that he couldn't read or write. It's thought that José Antonio Yorba—Vicenta's eldest son and Ramón's stepson—did all the paperwork for them.

After Ramón was ambushed and murdered in 1868, Vicenta (now twice widowed) took over ranching duties until she moved to Anaheim in 1868. In 1869, she "conveyed" the land to ex-Governor John G. Downey (also namesake of the town of Downey, California).

In 1888, Downey leased it to renowned cattle rancher Walter Vail, who died in 1911. A couple of years later, the family home became the quintessential "cowboy bunkhouse" under the operations of cattle baron George Sawday, whose operation remained at the Carrillo ranch until 1960.

Although the boarding house provided permanent residence for "career cowboys," some Hollywood cowboys—like Will Rogers and John Wayne—were known to pay a visit.

So what of the "Warner" part of the Warner-Carrillo Ranch House?

Most of the visible signs of it are gone. The historical records are scant. All we know is that a rancher and beaver trapper named Jonathan Trumbull Warner—who became a naturalized Mexican citizen of Alta California and changed his name to "Juan Jose" Warner (sometimes shortened to "J.J.")—lived either on the Carrillo's ranch property or on a parcel that abutted it.

The rest of the details are murky at best, but you can read about them here.

He's the same Warner of Warner Springs Ranch, and its stagecoach stop there, about four miles northeast of the Warner-Carrillo Ranch (and undisputedly a different historic property).

Why is the Carrillo Ranch inextricably linked to the Warner name? ::shrugs::

I'd driven by this site many times on my way to Anza-Borrego, but never stopped—for lack of time, maybe, or out of ignorance as to the significance of the site, even after its grand opening in 2013.

Or maybe I was just waiting for the right opportunity to visit, which was most certainly upon the occasion of these annual stagecoach rides.

Related Posts:

Photo Essay: The End of the Old West at Gilman Ranch

No comments:

Post a Comment