Its owner at the time—former bar regular Derek Schreck, who'd bought the establishment in 2013—was essentially marketing it as a tear-down, despite having promised patrons that he'd only sell to a buyer who'd keep it as a restaurant.

After Schreck took over in early 2014—later adding the attic speakeasy, The Vestry, in 2017—he was heralded for having saved the historic establishment. Everybody thought he would carry the torch from the three prior sets of owners—none of whom had changed it all that much.

Warner Ebbink and executive chef Brandon Boudet of Little Dom's and 101 Coffee Shop operated it from 2012-3. Closing night was July 7, 2013—and the occasion of my first visit ever.

It was like the last night on earth. They'd pretty much stopped charging the crowd and was just giving everything away. Actor Luke Perry (RIP) was bartending for part of that night.

Things were different, though, when Schreck shuttered the space in Summer 2018. There was no grand celebration. The lights went out with a whimper, as the staff eked out the last droplets of Tullamore Dew and gave branded glassware away to the few patrons who knew it was still open—at least kinda open, though the food had run out and the spirit had faded.

At the time, it was easy to think, "We've been through this before." Every time the tavern closes, it seems like it's going to be forever. But Bergin's always comes back.

Then the unthinkable happened: Schreck publicly opposed landmark designation. And that created a greater sense of alarm—because why would he care, unless he was hoping to sell to someone who planned to level it?

Don't worry—this story doesn't have a tragic ending, at least not yet.

But first, let's go back to the beginning.

Tom Bergin’s present‐day location on Fairfax near San Vicente was built and opened as a bar and restaurant in 1949. The two-story building, with its steeply pitched, cross‐gabled roof, was designed to look like a cottage that had been ripped right out of the pages of a storybook fairytale, evoking the rural countryside of Ireland in the Tudor Revival style that was popular at the time.

Its proprietor and namesake was Tom Bergin (1894‐1978), the Boston-reared son of Irish immigrants who worked for a time as an entertainment attorney. He leveraged his friendships with Hollywood elite like Bing Crosby to become a successful restaurateur.

Bergin operated his eponymous establishment—which earned the nickname the "House of Irish Coffee" sometime after the 1950s—until his retirement in 1973. He then sold it to bar regulars Mike Mandekic and T.K. Vodrey. (Vodrey continued at the helm until stepping down in 2011.)

Seven decades after it was dropped down on Fairfax without much else around, this Tudor cottage sure stands out on Fairfax Avenue—with its board and batten siding, stained rondel glass windows, and sconces that light up even when the place is closed.

Its hand‐hewn, clinker brick façade stands in stark contrast to the far more modern condo tower to the south and the multi-unit residences to the north...

...not to mention the nearest intersection that's littered with a gas station, fast food, and chain coffee shop and a chain pizza parlor.

And that's probably what draws people in—past the horse head busts (added in 2012), through the parking lot (which is really what makes this property valuable), and along the brick planters (also added in 2012).

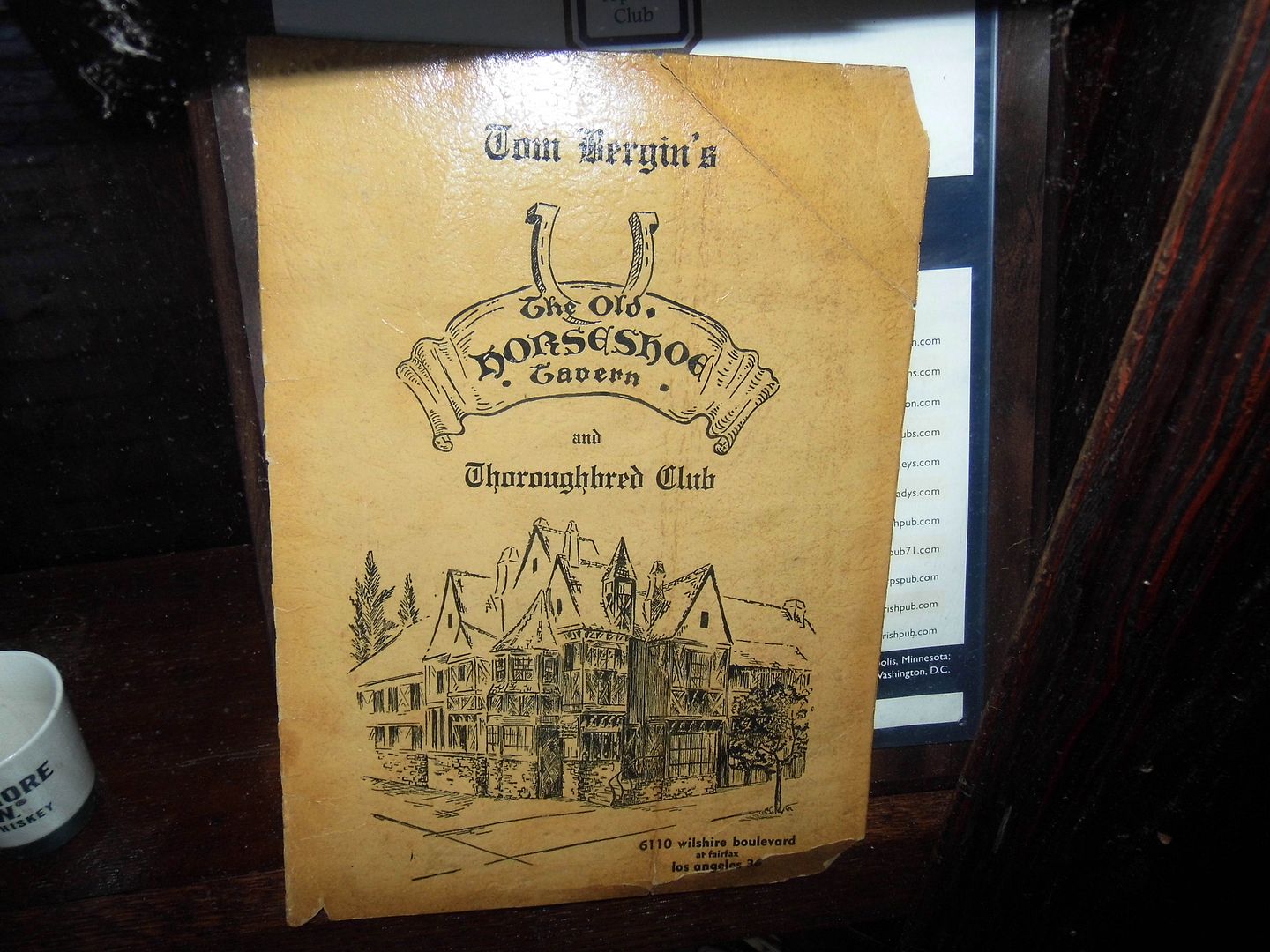

Why the horse heads? Well, Tom himself was an avid horseracing fan—and originally operated his establishment as Tom Bergin’s Old Horseshoe Tavern and Thoroughbred Club.

His first location had been located a block-and-a-half north at 6110 Wilshire Boulevard, at the intersection that now contains the May Company Building, Johnie's Coffee Shop, and the Petersen Automotive Museum.

When he relocated to a second location, he made sure he brought the horsemanship ambiance and old-world charm with him.

Back then, Tom Bergin's was more of a white tablecloth steakhouse sort of place, though its menu evolved to include more Irish pub fare like Reuben sandwiches, shepherds pie, and fish and chips.

After walking through the entrance (which has only been the front door since 2012), turn left for the main dining area, with its coved plaster ceiling, colored-glass windows, and one horseshoe‐shaped booth amidst more traditionally configured wooden banquettes.

Keep going, and you'll hit the private dining room, its wagon wheel-style chandeliers suspended from a vaulted ceiling that's supported by wooden rafters and beams. Cozy up in front of the clinker brick fireplace when a group hasn't reserved the room.

Back in the other direction—that is, if you were to turn right after entering—you'll find more hand‐hewn timbers covered in cardboard shamrocks, some stained brown from the days when indoor cigarette smoking was allowed. Each one is dedicated to a loyal patron of yore—though the path to getting your own name up there is somewhat unclear.

The horseshoe‐shaped, copper-topped bar that wraps around the room may have been relocated from the Wilshire location by devoted regulars—but the shamrock tradition hadn't begun yet, so you won't find their names anywhere on the ceiling.

At the far end—the one closest to Fairfax Avenue—you'll find more horseshoe‐shaped banquettes, though the really prized seating remains at the bar itself.

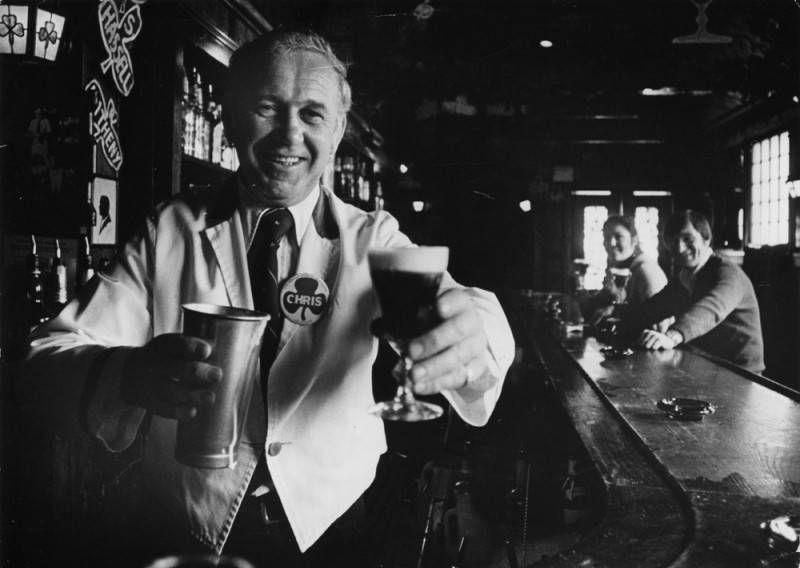

Photo: Bartender Chris Doyle, serves up quite an Irish coffee at Tom Bergin's House of Irish Coffee, circa 1979 (Herald Examiner collection, via LAPL)

If you manage to snag a bar seat, order a cream-capped Irish coffee—sipping the hot liquid through the cool topping, never stirring them together—and keep them coming.

For all these reasons and more, Tom Bergin's did, in fact, earn its landmark designation as a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument in June 2019.

In December 2019, it reopened under new ownership—and its manager, Fran Castagnetti, is providing as seamlessly consistent of an experience as possible (without, of course, the high-falutin craft cocktails and ultra-exclusive whiskey club that seemed to drag the business down more than lift it up).

Details of who the owner/developers are have been somewhat of a mystery—although it's likely Christopher Clifford of Colliers International. Tom Bergin's appears to be tied in with some Transit-Oriented Communities-related development that would involve building residential units on at least part of the parking lot.

The year 2020 has been as hard on Tom Bergin's as on any other eatery or drinkery in the wake of COVID-19 shutdowns and dine-in restrictions. It's successfully pivoted to takeout (pick-up and delivery), even offering Irish coffees "to go." And its existing liquor license for the parking lot—normally only used on St. Patrick's Day—has been a boon to expanding into outdoor dining and drinking.

But it's opened and closed and reopened again so many times over the last decade or so, lots of would-be patrons have been left confused as to its status. And Angelenos are easily distracted. You can't make them work too hard for anything.

I'm really pulling for the success of Tom Bergin's. I love that place.

And everybody loves a comeback story.

As Jonathan Gold wrote in the Los Angeles Times in 2013, "Bergin’s has always been decent, comforting and most of all there.... The Miracle Mile had boomed, fallen out of favor, and boomed again. The cool darkness of Bergin’s was one of the few constants."

For circa 2018 photos and lots of details as to the landmark nomination, click here.

Related Posts:

Photo Essay: A Vintage Drinking Den In a Historic Irish Cottage (Now Closed, Updated for 2019)

Photo Essay: A Spirited Jaunt to The Derby