And by then, I'd already booked myself on one traincation. I didn't have the time—or money—for two.

So I planned ahead this year and found myself once again in San Luis Obispo—twice in one year, after not having been at all for over seven years.

But this time, I was at the train station and ready to ride the rails.

The train we took isn't a special train, per se.

It's one of the modern-era, double-decker Amtrak Coast Starlight trains, outfitted with sleeper cars.

Screenshot: Google Maps

The real attraction for me was the route the train would take on the way to Paso Robles.

Stenner Creek trestle, built 1904

It's a steep incline (and decline) known as the Cuesta Grade, a seemingly impassible stretch of terrain that was conquered by railroaders at the turn of the last century and cuts through the private La Cuesta Ranch and passes Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo and the California Men's Colony.

Engineers had to blast a lot of rock to get a train to make the twists and turns necessary to ascend and descend the grade—over million cubic yards, some of which included California's state rock, serpentinite (composed of serpentine minerals).

Just like a hike, the most efficient way to take the 1140-foot elevation change is through a number of switchbacks...

...that take the train up into the Santa Lucia mountain range above Highway 101, which curves around the bend below.

And successfully making that difficult climb requires traveling into hand-drilled, redwood-lined tunnels...

...and out...

...and back in, over the course of 16 rail miles (though only 10 miles by car) at no more than 30 mph, several times over.

It's actually one fewer than originally planned, as one such tunnel caved in on itself in 1910. Unable to repair it, the railroad simply bypassed it—though you can see the sealed entrance today.

Although the train technically also passes right by the Pomar Junction vineyard, Amtrak doesn't like to make unscheduled stops at unofficial stations. So we took a bus from El Paso del Robles.

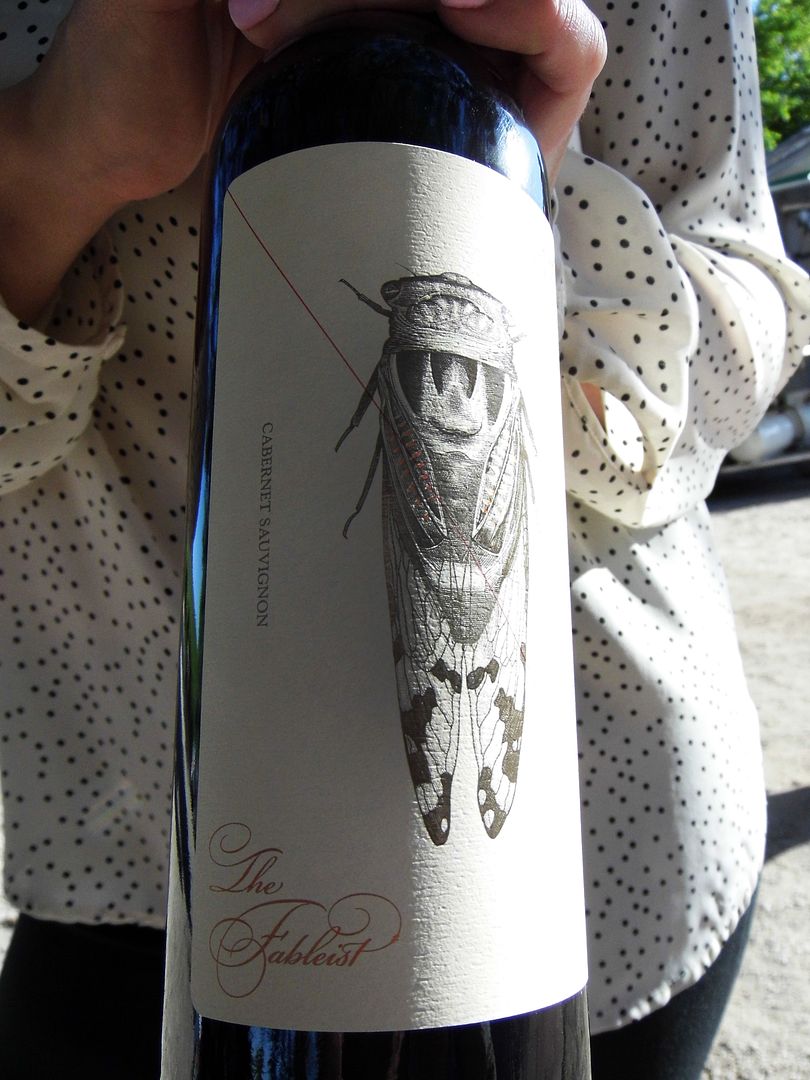

At the end of the line, we arrived at the tasting room of The Fableist, whose wines are each inspired by Aesop's Fables, like the Cabernet Sauvignon's take on "The Ant and the Cicada"...

...and the Gruner Veltliner take on "The Fox and the Stork."

Pomar Junction still owns the vineyard there and makes its wine from its grapes, but Fableist has taken over its tasting room.

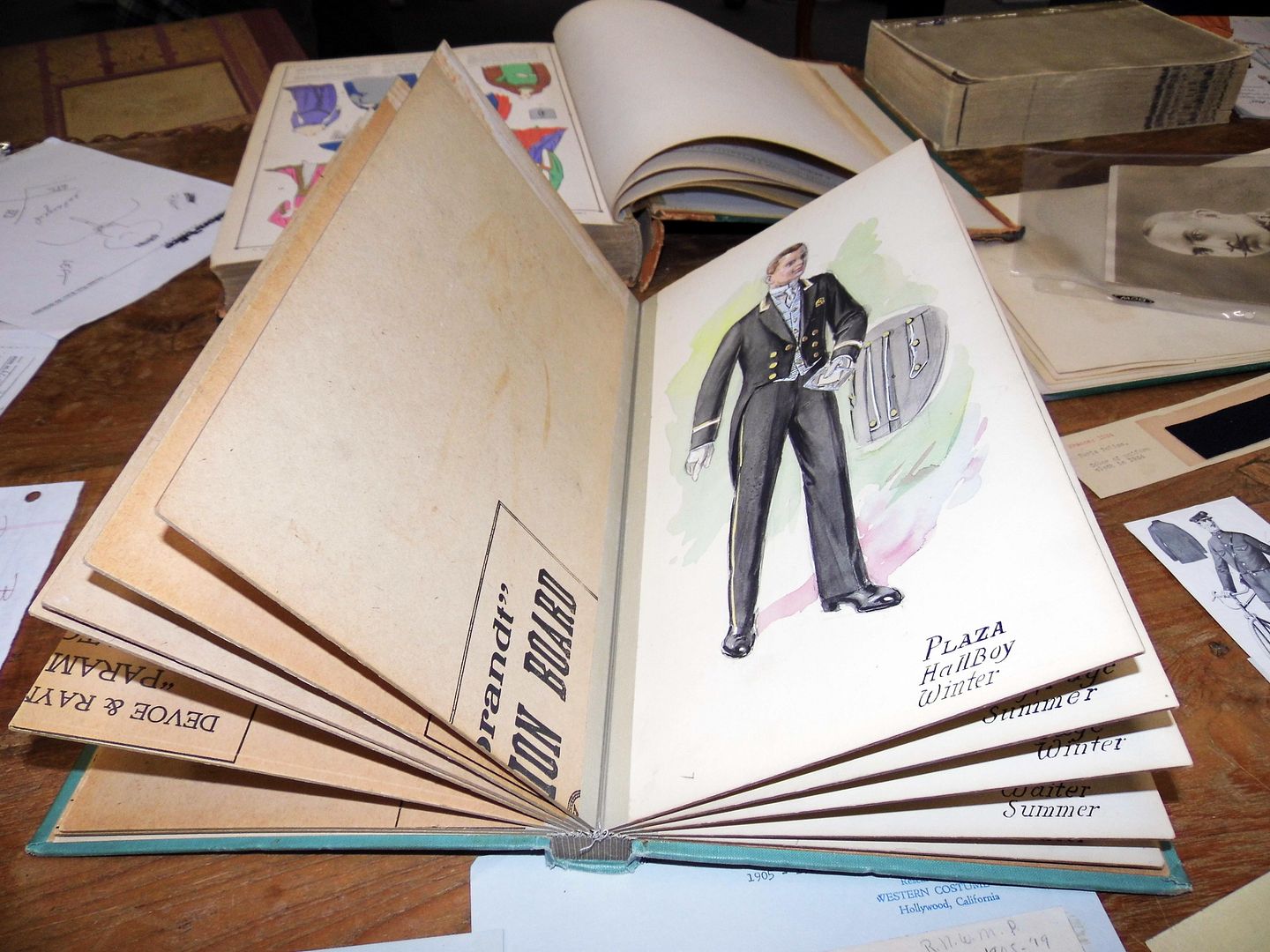

And fortunately, it's preserved the "train stuff" that can be found on the tasting tables...

...and throughout the grounds.

It's also continuing Pomar Junction's "Train Wreck Fridays"—the party we stumbled into and then wholeheartedly joined.

After tasting a few Central Coast wines and knocking back a couple of full glasses...

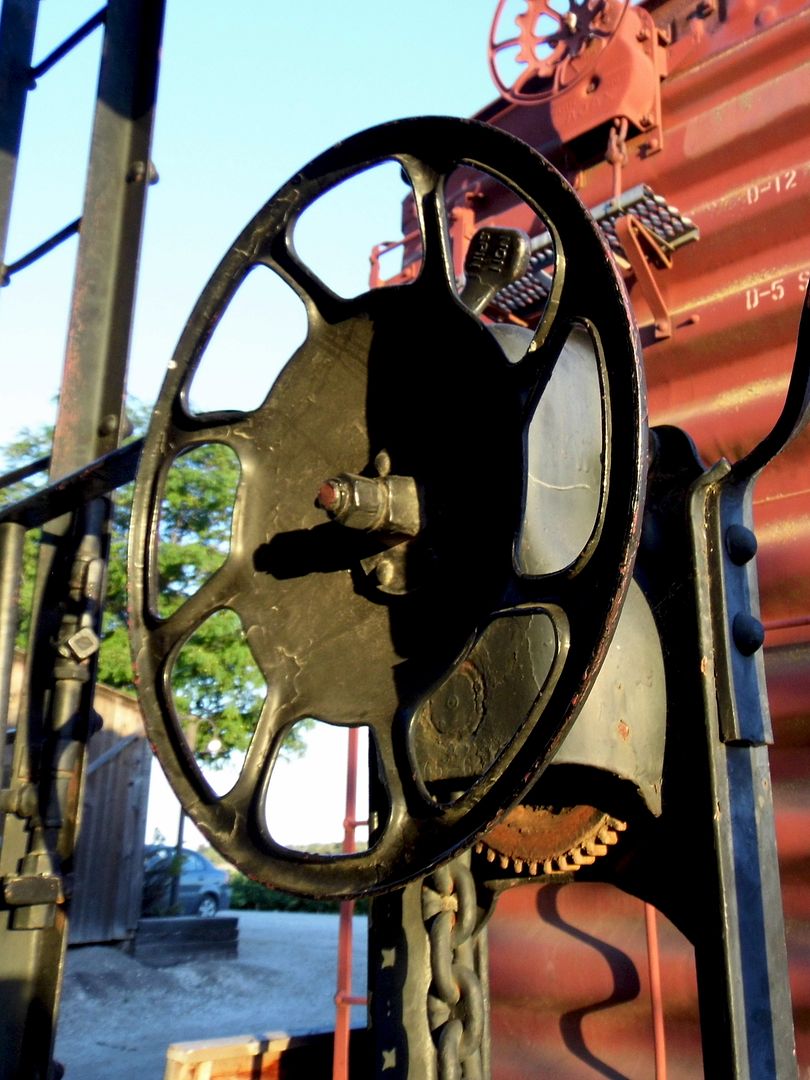

...it's just my style to skulk around some rescued and relocated trains...

...though they may be considered "condemned."

In fact, that's even better.

In 1886, the Southern Pacific Railroad had reached Paso Robles, but it wasn't until 1894 that it met up with the Pacific Coast Railway in San Luis Obispo, thanks to the construction through "La Cuesta."

Although Union Pacific currently owns these rails and operates its freight trains, it's Amtrak that operates passenger trains through there, from LA to Seattle—which means any ticketed passenger can experience this engineering feat firsthand. It just helps to know what you're looking at.

For a detailed description of the route, click here.

Related Posts:

Photo Essay: An Engineer's-Eye View Along a Desert Rail Line

Photo Essay: Riding a Ghost Train and Bunking Up In a Caboose (Or, This Is What A Traincation Is All About)

Photo Essay: The Terroir of Baja Wine Country