And I've always gotten a kick out of wearing stage makeup or getting camera-ready for a TV appearance or film cameo.

But otherwise, I've kept mostly to lipstick or, in more recent times, shiny pink lip balm, and a little line from an eye pencil or pen. I didn't start wearing mascara until I got contact lenses around age 30 because my naturally long lashes would just scrape against the inside of my glasses. And that just wasn't cute at all.

The few times my mother ever "went out" when I was a kid—maybe to my father's workplace Christmas party—she had her standard sparkly blue eyeshadow and under-eye highlighter (after all, it was the late '70s/early '80s), punctuated by some eyeliner and mascara.

Virginia Weinheimer, age 18 (circa 1936)

Like me, cosmetics entrepreneur Gabriela Hernandez was inspired by her grandmother's beauty routine—one with a simple glamour that's somehow disappeared from modern makeup. With that vintage aesthetic in mind, she created her beauty brand, Bésame Cosmetics, and launched a single red lipstick circa 1920—later recreating historical details from several decades for contemporary versions of an entire line of her own makeup formulas.

A unique combination of artist and historian, Hernandez has found herself in the role of "color detective"—analyzing old lipsticks and other cosmetics to unveil what the pigments are underneath. Because as anyone who's ever tried to wear red lipstick knows, no two reds are exactly the same.

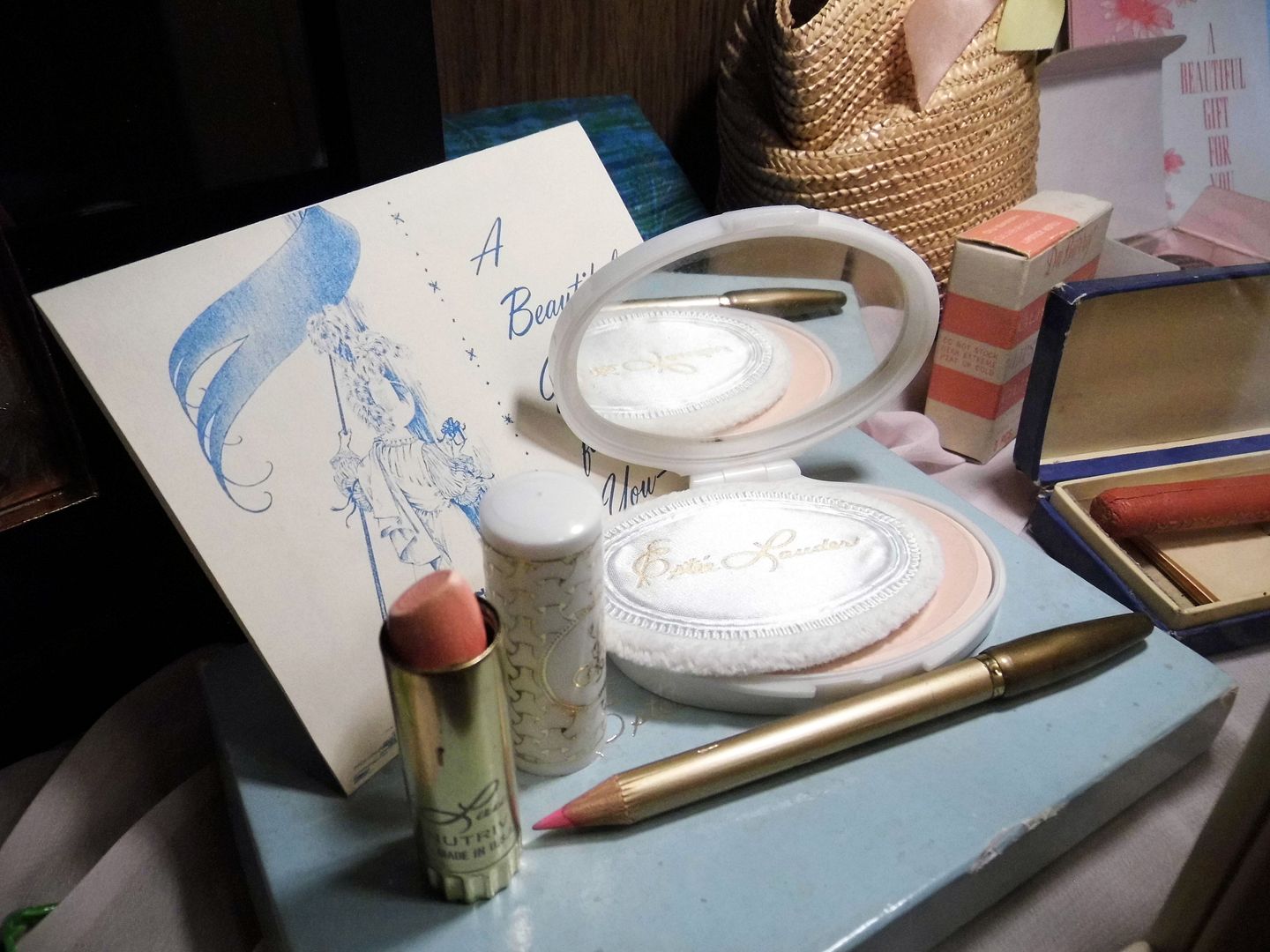

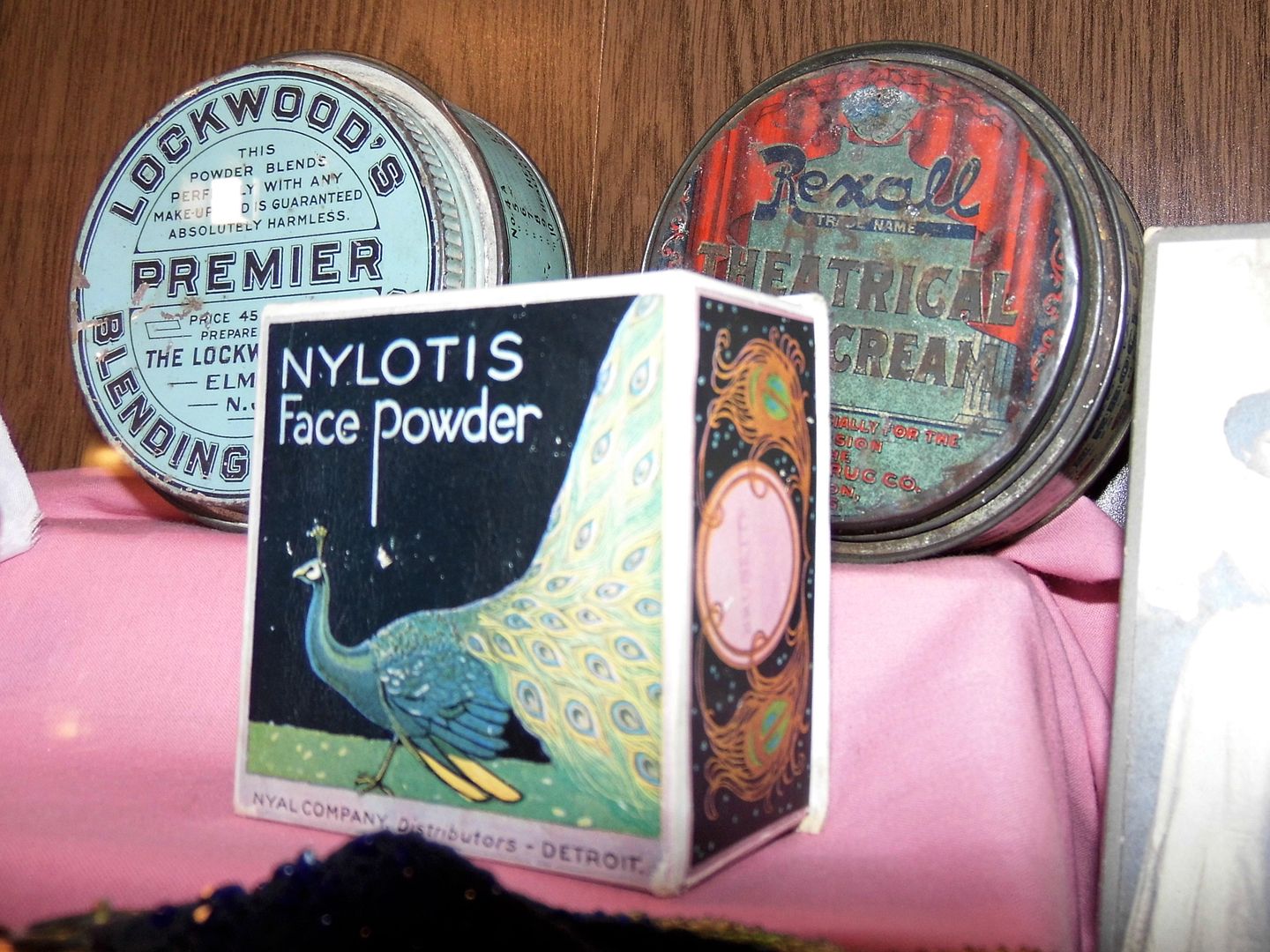

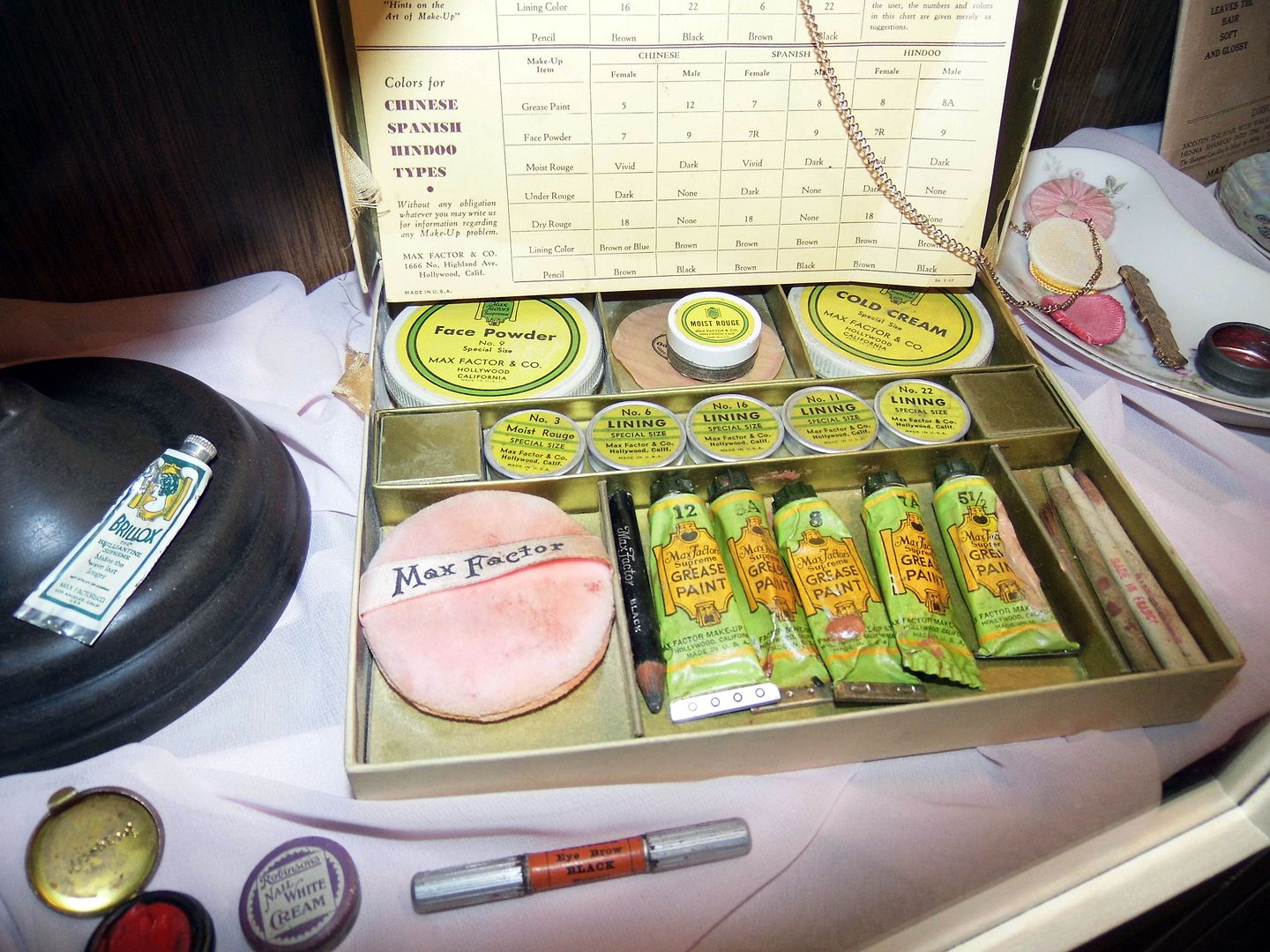

In the back of her Burbank storefront, Hernandez has got a kind of "hall of fame" of vintage cosmetic products—some of which might not be recreated exactly the same way because of where the pigments were originally sourced from (like, say, crushed bugs).

You can sign up for a makeup class, photo shoot, or makeup application in that back room when the store is open...

...or you can leisurely browse the front room...

...where Bésame-branded cosmetics are sold behind a nice old-fashioned makeup counter on one side...

...and the other side displays selected makeup trends from the year 1900 to today, encased in glass cabinets in a kind of mini cosmetics "museum."

Of course, Max Factor is represented here, as are Avon and Cutex...

...and old "cake" forms of mascaras, like those sold under the brand name Winx.

Practically everything started out as a powder in some form or another, whether loose or compressed...

...and the formulations evolved as makeup started to be worn by more than stage or film actors...

...and entered the lexicon of "everyday" beauty.

I don't ever remember seeing my Grammy without her red lipstick on. And I rarely saw her outside of her own home.

Meanwhile, I haven't worn any makeup for two and a half months. And I'm not sure when I'll have the opportunity to again.

When I'm ready to emerge back out into the world—whatever that world will be like—maybe I'll splurge on something nice from Bésame, like its rouge brush made from soft, cruelty-free hair, and featuring a contoured wooden handle.

If I watched much TV, I might try to look like Jessica Lange on American Horror Story: Freak Show

or the multiple actresses featured in the Netflix series Hollywood who wore multiple shades of red from Bésame.

Or one day, maybe there will be an occasion special enough for me to get my makeup done there.

In the meantime, it's reassuring to know that someone values the beauty of "Old Hollywood"—and that there's enough of a consumer market to snap up the heirloom-inspired products that continue to be released.

Related Posts:

Photo Essay: The Jewel Box of the Cosmetic World and Its Pink Powder Puff

Meditations on Chroma