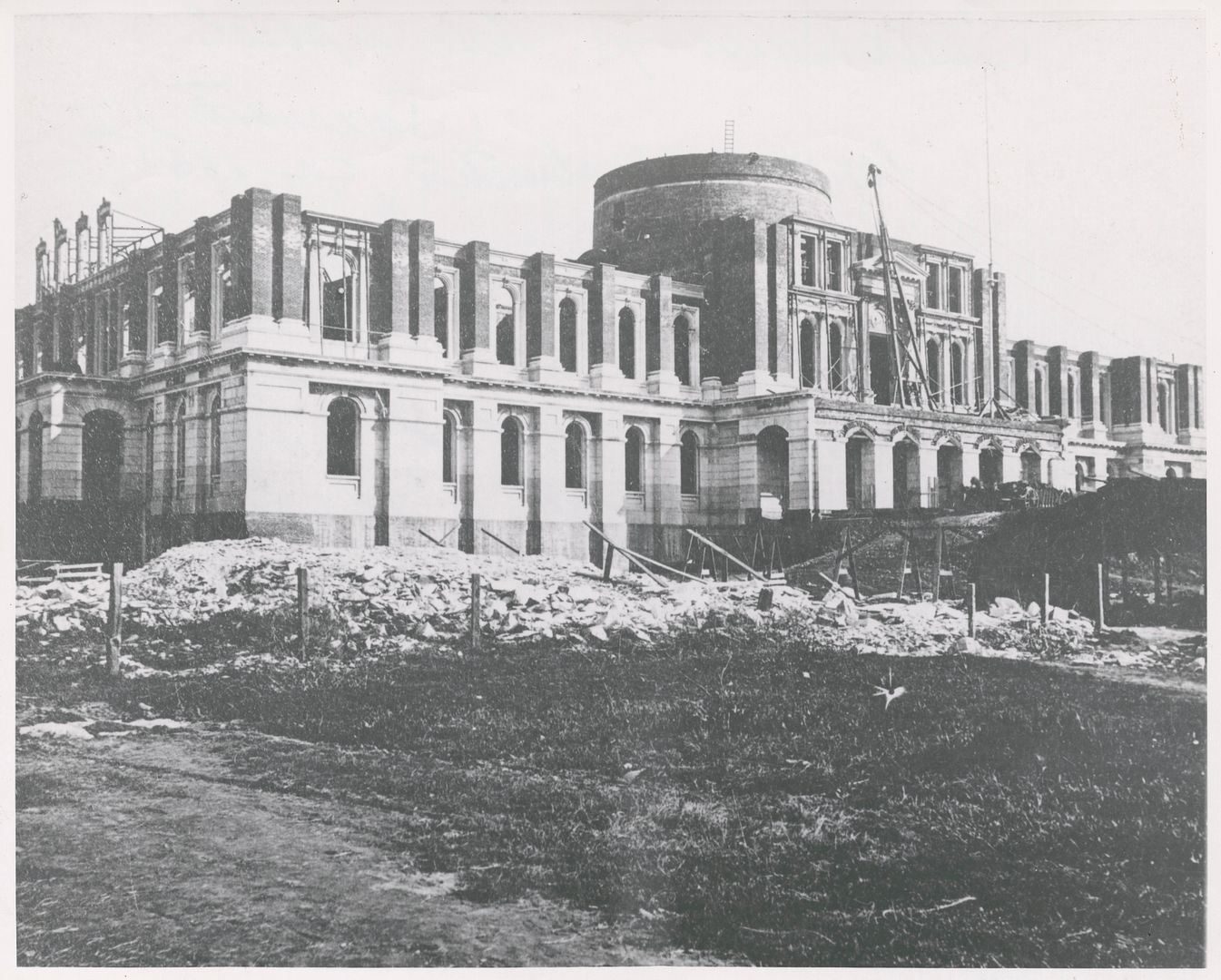

Construction photo: McCurry Foto Co. via California State Library

While working under San Francisco-based architect M. Frederic ("M.F.") Butler, Clark’s drawings of the neoclassical monument (based on the U.S. Capitol building in Washington, D.C.) were soaked in the floods of 1861-2. On top of that, the Civil War was already well underway, causing a shortage of building materials that Clark could no longer bring from the East Coast to California.

Perhaps the proverbial nail in the coffin occurred in the wake of Abraham Lincoln's assassination in 1865, when Clark was found guilty of "disloyalty to the Union" for hiring “known secessionists” and supposedly saying that he didn’t care which side won the Civil War.

By the time Clark was exonerated for his treasonous statements, it was too late—he was already dead. And his former assistant, Gordon P. Cummings, had taken over as the supervising architect, completing the project over two non-consecutive stints (1865-1870 and 1872-1874).

Between the two of them, the end result is a somewhat incongruous mishmash of Greco-Roman influences—with Cummings shifting from Roman to Greek, Doric capitals giving way to Corinthian columns.

And while Clark had begun to use granite, Cummings switched to cheaper materials simulated to look like granite. Even the granite itself doesn't match—at least on the lower floor, where the governor's own railroad investments influenced which quarries it would be sourced from.

As the California state capitol building was under construction from 1860 to 1874—the last eight years proceeding without its original supervising architect—Clark rarely gets credit for its design.

At a cost of $2.5 million—compared to Clark's original budget of $100,000—the final result wasn't exactly what the architect lost his sanity trying to accomplish.

One posthumous victory for Clark came on October 29, 1871, when a gold-plated copper ball was affixed as he crowning ornament of the cupola at the apex of the Capitol. Nearly three feet in diameter and reminiscent of a gold nugget, he'd included the ball in his original plans—and his replacement, Cummings, tried to replace it with a bronze statue, a more traditional choice.

The ball won out—which seems appropriate, since the capitol's dome and rotunda are the crown jewels of Clark's design. Emblematic of the use of religious architecture for state capitols in the 18th century, the rotunda rises 120 feet high; and its dome features frescoing that reflects the Renaissance Revival style popular during the 19th century. But the frieze at the base of the dome is truly Californian—with depictions of grizzly bears, our state symbol and state animal.

Clark himself was a Freemason and managed to incorporate a Masonic floor pattern in the circular room below the dome, surrounding the neoclassical statuary group, Columbus’ Last Appeal to Queen Isabella (carved of Carrara marble by sculptor Larkin Goldsmith Mead and gifted by Darius Ogden Mills in 1883). The Capitol's dedication ceremony was even Masonic.

The current building has served as California's state capitol building since 1874—but it almost didn't happen at all. The state government could be found "roving" from city to city within California over the course of a good two decades. First, the State Capitol was in San Jose from 1849-51. It moved to Sacramento for five months in 1852. Otherwise, from 1852-3, it was located in Vallejo.

The Benicia Capitol Building (circa 1853-4) is the only edifice still standing outside of Sacramento. In 1958, it was rededicated as state historic park—and for the occasion, the state capital was moved there for just one day (except for that other day in the year 2000, for the 150th anniversary of California's statehood).

replica ceramic tiles originally installed in 1896 from the Mosaic Tile Company of Zanesville, OH

Sacramento was named permanent seat of the California government in 1854—but even that wasn't permanent. The December 1861 flooding sent the state government packing for San Francisco in 1862, while the current Capitol Building was under construction.

The current capitol was almost demolished in 1975—but instead, a pricey renovation returned it to its grandeur circa 1906, the year of the San Francisco earthquake and fires. That meant rebuilding grand staircases that had been removed; reinstalling its California poppy mosaic tile floor; and recreating the 1906 governor's offices (which had been used until 1951) and 1906 treasurer's office (which once held $8 million in gold and silver coins, before they were transferred to a bank the following year).

The Senate Chambers on the south side and the State Assembly on the north side of the building currently look as they did in the late 1800s, with color schemes that can be traced back to the British Parliament (red=House of Lords and green=House of Commons). Coffered ceilings loom over desks carved out of walnut and restored to their original splendor.

Outside of each gallery is the California state seal, fabricated out of stained glass and lit by electricity, not sunlight. Installed in 1907, they depict the Roman goddess Minerva under an arc of 31 stars (the of states in the Union upon California's annexation) and surrounded by such California state symbols as the grizzly bear, a grapevine, a (gold?) miner, and the Sierra Nevada mountain range. Of course, there's also our state motto, "Eureka" ("I have found it").

The tradition of commissioning portraits of California's governors wasn't formalized by the State Legislature until 1931, but you can still find portraits of 38 governors displayed throughout the West Wing—including Ronald Reagan and yes, Arnold Schwarzenegger.

After all, it's got to portray some recent history.

I wonder how many other people have been driven insane by their association with the California state government?

Related Posts:

Photo Essay: Glimpses of Sacramento, California

Photo Essay: The First Cathedral of the Colonies

Photo Essay: How A Metaphysical Religious Sect Brought a Glimpse of DC to LA

Photo Essay: City Hall at Sunset (Updated for 2017)

Nice try at continuing the make-believe. That man didn't design or construct that building. Take another look.

ReplyDeleteComing from California I should have expected this gathering of ideas and make believe fitting of the fiction the permeates from your state. Bravo sir. This is a travesty. That we're supposed to believe this is an accurate account of the construction of that magnificent building is just plane sad. That man didn't construct or design this building. Take another look at it.

ReplyDelete