The only challenge was finding someplace on my list that was actually open and unlocked—and where I was not only allowed to be, but also safe to be.

I didn't have to go far to finally make it to the sculpture garden on the UCLA campus.

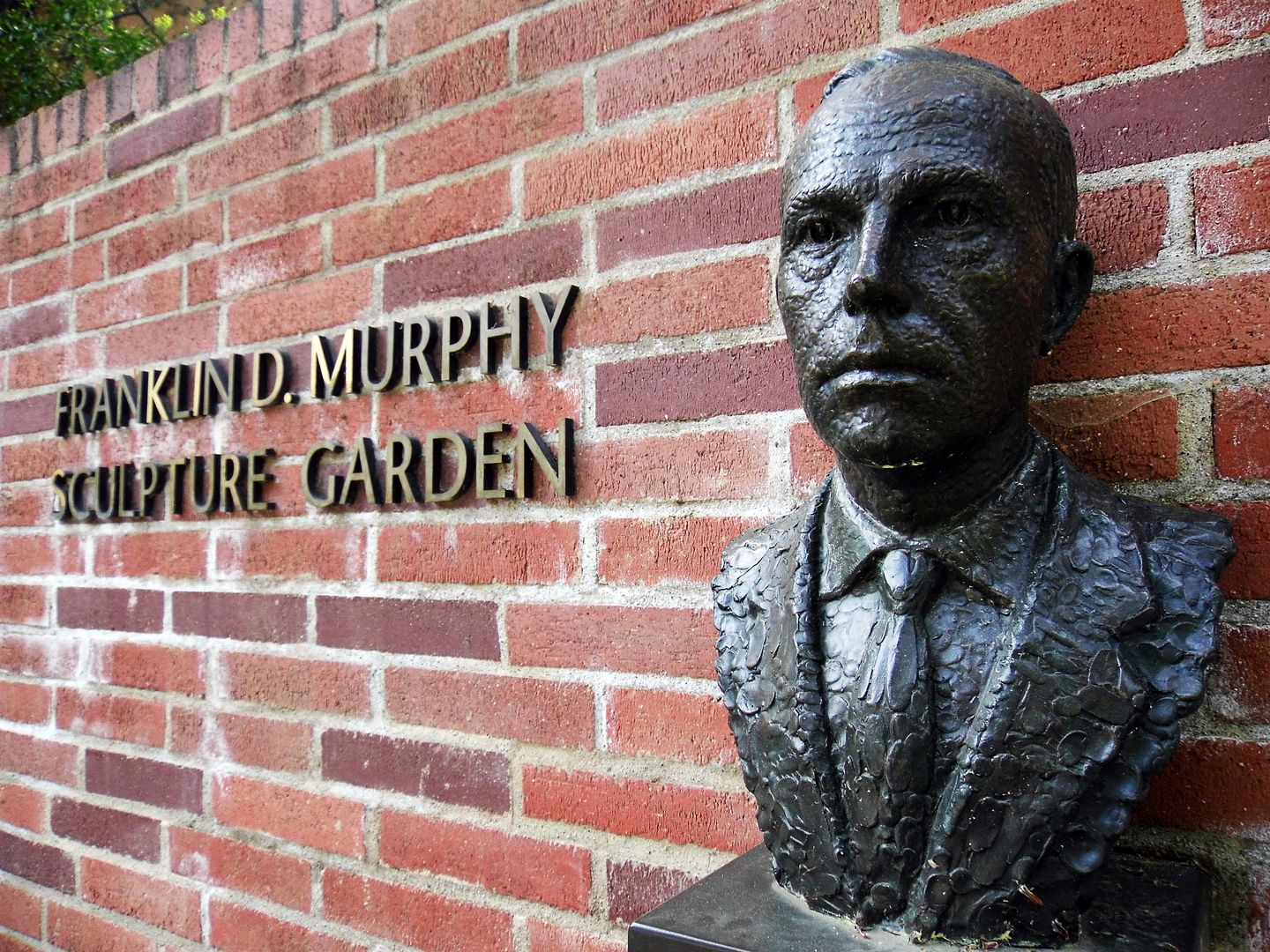

Located on UCLA's north campus, it's a 5-acre sprawl of both figurative and abstract works by sculptors from all over the world—like Italian Pietro Consagra, whose Colloquio Duro ("Difficult Dialogue") bronze relief from 1959 adorns the same wall as the bust of Chancellor Murphy himself (by Eldon C. Tefft, circa 1960).

It's hard to believe that American sculptor Dimitri Hadzi's Elmo III, circa1960, now stands where there once was a parking lot.

Supervisory landscape architect at the time Ralph Dalton Cornell (of the firm Cornell, Bridgers, and Troller) had to design the garden without knowing what was going to be placed there or where. And yet every placement—like British sculptor Eric Gill's Mulier ("Mother," undated but probably prior to 1911) at the head of a fountain in front of UCLA’s Young Research Library—feels just perfect.

Some of the standouts among the more than 70 sculptures in the garden—for me, anyway—include the bronze Maja by German sculptor Gerhard Marcks (circa 1941)...

...the bronze Queen of Sheba by Alexander Archipenko, a Ukrainian-born American (circa 1961, and one of an edition of eight)...

...and Californian surrealist Jack Zajac's Bound goat, Wednesday (circa 1973).

Gerhard Marcks Freya, 1949

...though not all the pieces in the collection exactly match the setting, like The Walking Man.

Located at the end of an allée of South African coral trees, Auguste Rodin's L'homme qui marche was first started by the French sculptor in the late 1870s.

A headless depiction of St. John the Baptist also without arms, it's considered an "unfinished" work of Rodin. This bronze cast—one of an edition of 12, #7 located at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena—is dated 1905.

It seems to lead the way towards the campus's Broad Art Center...

...whose front plaza is anchored by the site-specific installation of T.E.U.C.L.A. (circa 2006) by American artist Richard Serra.

The 42.5-ton piece is part of Serra's Torqued Ellipse series, which he started in 1996—and his first to be on permanent public view in Southern California.

It predates the 360-ton steel Connector installation at Segerstrom Hall in Costa Mesa, Orange County by mere months.

And like the rest of the pieces in the series, Serra created this installation by twisting huge COR-TEN (or "weathering") steel plates into circular or elliptical sculptures that you can walk into and gaze up at the wide-open sky.

Its characteristic dark patina of rust—with nary an aberration in the color—could take as long as a decade to develop and fully oxidize. (So no touching, please!)

The Serra sculpture also serves as a kind of gateway to Henri Matisse's Bas Relief I-IV (The Back Series)—four bronzed plaster casts that were first modeled for and created, left to right, in 1909, 1913, 1916-7, and 1930.

In 1950, three of them were cast in bronze. Five years later, the fourth one was discovered and also cast in bronze.

These monumental sculptures are also Matisse's largest—with other complete sets housed at MOMA in NYC, the Tate in London, and other major museums in Paris, Zürich, Stuttgart, Houston, Fort Worth, and Washington, DC.

The collection seems particularly well-curated when you encounter works by certain artists that come full circle—like Noble Burdens (Les Nobles Fardeaux, circa 1911) by Antoine Bourdelle, a teacher of Matisse and student of Rodin.

And yet the French masters intermingle with Latin American artists, like the Costa Rican-born Mexican sculptor Francisco Zúñiga, whose Mother With Child At Her Hip (Madre con niño en la cadera, circa 1979) exemplifies his artistic devotion to the female form.

My favorite of all the works, though, was the first one I saw—well, caught a glimpse of as I was driving past a pedestrian entrance in search of a parking spot.

Vienna-born Anna Mahler—daughter of the Austrian composer Gustav Mahler—is the sculptor behind the stone carved Tower of Masks (circa 1961). She also taught art at UCLA in the 1950s, after relocating to Los Angeles from Europe.

The 15-foot-high, 28-ton limestone totem was actually the first sculpture to be installed in the garden—in 1961, six years before its official dedication.

But its been relocated from the Theater Arts Court of Macgowan Hall, part of the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television—a seemingly fitting setting for an assemblage of theater masks.

The stone pillar is now just east of the official boundaries of the sculpture garden, on an island land-locked between the Macgowan Hall Bus Turnaround and Charles E. Young Drive E.

I spent a long time at the UCLA sculpture garden—where else did I have to go?—but I still sense that I only saw a fraction of it.

I don't know what took me so long to get there, but I'm grateful for the cleared schedule that allowed me to finally make it.

Related Posts:

Photo Essay: The Donald M. Kendall Sculpture Gardens

Photo Essay: Mildred E. Mathias Botanical Garden, UCLA

No comments:

Post a Comment