I've already posted about a couple of adventures I've had recently with Rim of the World Historical Society, based in the mountain communities of the San Bernardino Mountains.

But I haven't shared why I joined the historical society in the first place—and it starts with Huell Howser, the local celebrity of regionally-focused TV shows that highlight various California landmarks and attractions.

One of the sites he visited for one of his episodes of California's Gold was Lake Arrowhead, California—not just the town, but specifically the lake.

And specifically part of the manmade lake's infrastructure—starting at a stone structure that contains a 19th-century elevator down a 185-foot vertical shaft that leads to "Tunnel #1."

You see, Lake Arrowhead was created around the turn of the last century as part of a way to harness the water rights of the area and bring some of that water down into the citrus groves of San Bernardino—a plan hatched by financiers James Gamble of Procter & Gamble and James Edmund Mooney of Cincinnati, who formed Arrowhead Reservoir Company.

But the proposed irrigation project would've meant redirecting water away from its natural drainage basin and violating the riparian rights of some of the landowners in the Mojave Desert communities of the watershed north of the mountains. So, some of them (like Hesperia Land and Water Company, which you can read about here and here) sued in 1909 for the right to appropriate the water supply and won years later.

And then perhaps the final nail in the coffin was the California Water Commission Act of 1913—which took effect December 1914 and stipulated that water could not be taken from downstream and brought upstream. And while many creeks and rivers do run from north to south, those that feed the area (namely, Deep Creek/the East Fork of the Mojave River) run south to north—making the Inland Empire technically upstream from the headwaters.

Those original plans were abandoned thereafter—but only after certain aspects of the lake had already been built, like the tallest concrete tower in the world (the "outlet tower," which still sticks out of the lake water's surface), the elevator shaft, and Tunnel #1, which the shaft connects to.

Fortunately, that infrastructure wasn't destroyed—and as it turns out, Rim of the World Historical Society conducts occasional tours of Tunnel #1 for its members.

And this past August, after having joined the society without hesitation, I met up with the group to scramble down some steep inclines...

...and along dirt roads where most vehicles dare not tread (and maybe aren't allowed to anyway)...

...towards Willow Creek (formerly known as Guernsey Creek).

We passed some ruins, including the remains of a 1920s-era septic system—which were the first sign of what was supposed to have become the biggest irrigation project in the country.

We then arrived at the (locked) Outlet Tunnel #1, which had been designed as a water diversion tunnel—one that needed to be built and functional before the dam construction that would block the flow of natural water sources to create an artificial reservoir.

It would literally divert water from its natural path—that is, coming from Little Bear Creek (a tributary of Deep Creek)—so the dam builders could work without getting wet.

Construction began at both ends of the tunnel in February 1892—mining through bedrock, primarily by hand picking but also with the help of some steam-powered tools and explosives. It took about three years for the northerly and southerly tunneling efforts to meet in the middle.

Getting to enter that tunnel is really special. Down there, it felt like being in a mine shaft. I still can't believe they let anybody inside.

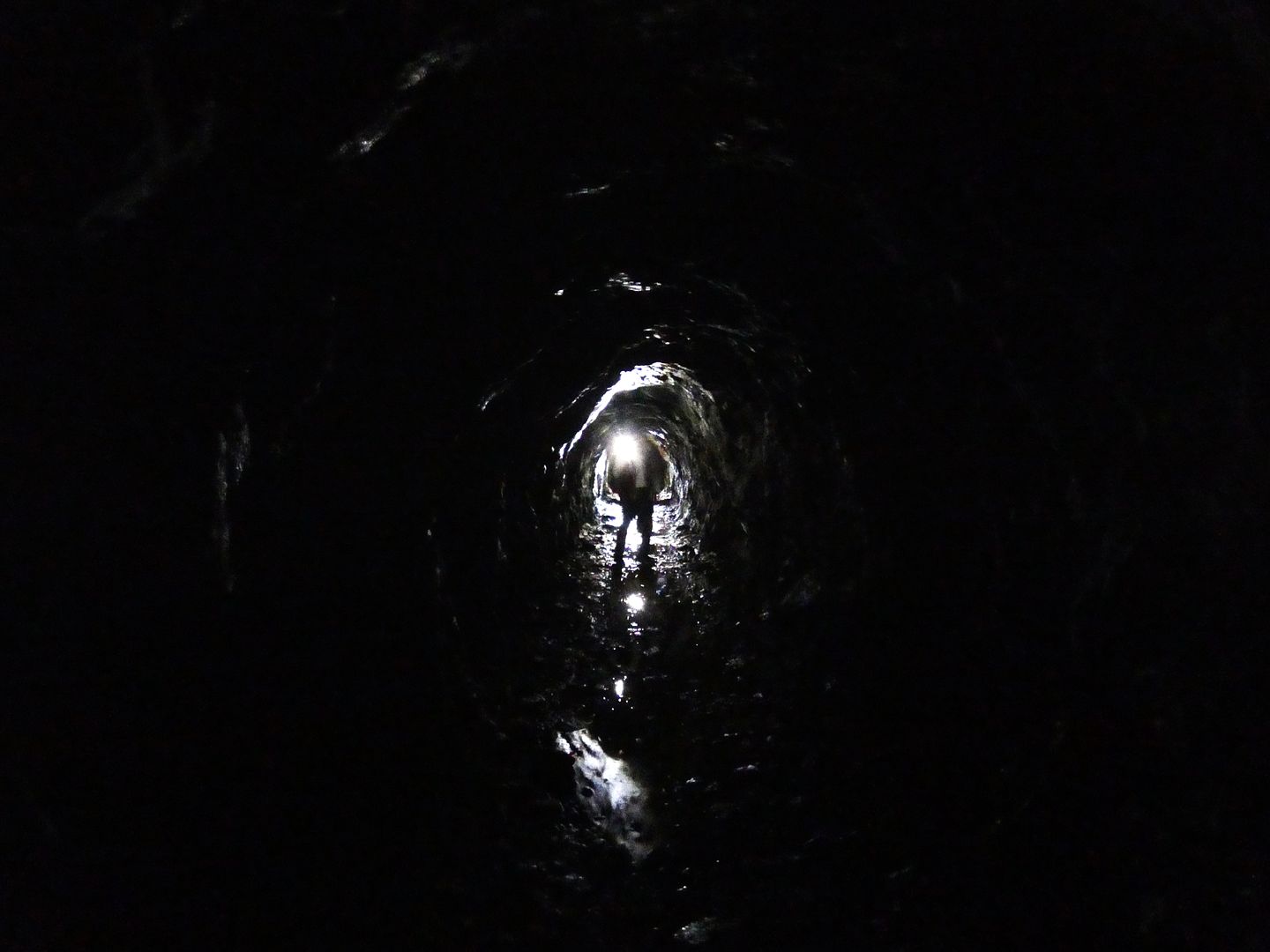

It's pitch black, save for flashlights and headlamps reflecting off the droplets of seepage.

And even though there's no natural light down there, some life still manages to prevail—like the lichen that grows on the walls.

Walking even a short distance was treacherous and arduous and took hours.

Underfoot, it's wet and rocky, with few level platforms and lots of trip hazards—but during our tour, I couldn't always grab onto the wall for support. I had no idea what I'd get a handful of!

Coming upon a pile of rocks, In didn't know whether they were left over from the initial mining effort (though there are no tailings to be found anywhere else) or had crumbled in the meantime—as a result of a seismic event or perhaps as an indication of some structural instability.

Some parts of Tunnel #1 look entirely completed and are stunning in their horseshoe shape—six feet wide at the top and five feet wide at the bottom, with about six feet six inches in height.

But only about 20% of the tunnel is finished—that is, lined with concrete—while the rest is raw with jagged rock, despite the original plan being for the entire thing to be lined. In the end, they only lined the tunnel where the rock was considered "unstable."

By the time we reached what someone had marked as the half-way point in graffiti, it already felt like we'd been walking forever, trying to keep our ankles from rolling and breaking.

Fortunately, we stopped occasionally to marvel at the enormity of the project and to examine some of what the tunnelers and drillers had left behind...

... including wooden hooks for kerosene lamps...

...old candle mounts (as there was no electrical light available down there at the time)...

...other pieces of old wood...

...and drilled holes that would hold the dynamite sticks for blasting.

I had decided not to carry a flashlight myself, as I wanted both hands free to catch myself when I tripped—and I tripped often—and to take photos. (I'd forgotten my headlamp at home.)

But I could occasionally look behind me to get my bearings, thanks to the lights cast by my fellow historical society members also making their way through the tunnel.

It was impossible to keep our feet dry, with the varying depths of mucky water underfoot. Even the guy in hip waders said that the water would splash up into them from the top. I didn't even try to stay dry, instead making myself wetter by stomping my feet to make sure I had secure enough footing.

Sometimes, the water was so deep, it was better to simply drag my feet along the bottom, feeling for any unexpected drop-off.

The farther we got into the tunnel—that is, the farther south we went, and the closer to the actual lake we got—the more the solid granite gave way to granite with talc seams.

Some of the veins in the granite rock almost looked like quartz—and quartz veins are sometimes an indication that there are gold deposits in the rock.

But we weren't there for prospecting. We'd gone underground to experience just a sliver of the proposed 60 miles of tunnels and other conveyances that would move water into and out of Lake Arrowhead Reservoir and six other "lakes" (a.k.a. reservoirs). (Just 6 miles of tunnels were actually completed.)

It's an experience few have ever had. And I felt grateful to count myself among the few.

The dam was completed in 1919, with the lake almost full of water—two years after a Supreme Court decision barred the Arrowhead Reservoir and Power Company from pumping the water southwards.

That's one of the reasons the tunnel is essentially empty today—and how we can walk through it (without, you know, drowning).

But it could be used to drain the lake in anticipation of a potential flooding event, like an earthquake or a dam break.

From the shaft to the tunnel entrance, the elevation drops just 2 feet for every 1000 feet in length so the water can move by gravity from the lake and dump out into Willow Creek. (You can still see some old plumb bobs, which helped the tunnelers maintain a more or less straight, level line.)

Tunnel #1 is about 3800 feet in length (3/4 mile)—and towards the end of it, we came across some of the cast iron piping that was installed back in 1905 and was controlled by a number of hydraulic gate valves, right below that vertical shaft that Huell Howser entered for his TV show (scroll down to watch episode).

That explains all the hydraulic fluid that was soiling our shoes, hands, and clothes.

We didn't make it all the way to the end of the tunnel, directly below the vertical shaft (where we would've found a pool of water several feet deep), so at the pipes we turned around and quickly made our way back the way we came—until literally reaching the light at the end of the tunnel.

Upon completing my tunnel adventure, I was awarded a certificate for the Minus 185 Club of Lake Arrowhead by the Arrowhead Lake Association (ALA), the homeowners association that owns the property surrounding and including the tunnel. The "185" refers to how deep the tunnel is underground (at least at the bottom of the vertical shaft.)

Huell and his cameraman Luis got the exact same certificates. And I'm just tickled pink.

In his episode (embedded at the bottom of this post), Huell Howser describes walking through Tunnel #1 as "It's fun, but it gets old real fast." And that's how I felt about it at the time, too.

But reflecting back on my visit, which was just over a couple of months ago now, my mind is still blown over what exists hiding in plain sight out there—and what I got to see.

And I haven't had enough of the area yet—because I'm excited to get onto the lake next summer. Generally, lake access is limited to lakefront homeowners, but there is a tour boat that's open to the public.

Stay tuned.

See above for Huell's California's Gold episode...

...and a video from another attendee's experience of the Rim of the World Historical Society tunnel tour.

Related Posts:

That is SO COOL!

ReplyDeleteGreat adventure, Sandi, and great story!

ReplyDeleteGlad there wasn't an earthquake--welcome back to the surface!

ReplyDeleteI seriously thought about that down there!

Delete