After I moved to LA and began exploring Southern California, I learned about the Arts and Crafts Movement by visiting The Gamble House, the Judson family's historic stained glass studio, and Ernest Batchelder's Pasadena home, adjacent to Bungalow Heaven.

It never occurred to me that there'd be any Arts and Crafts activity anywhere in New York State, where I grew up. (I guess I forgot about Stickley.)

But as I was traveling in and out of Buffalo on my way to make a hometown visit to Syracuse a couple of months ago, I arranged a visit to what I discovered is a federally recognized center of the American Arts and Crafts Movement.

It's the national historic landmark (designated 1986) known as "The Roycroft Shops" (1895-1938)—located in the Buffalo suburb of East Aurora, in Western New York.

The word "Roycroft" is reportedly a portmanteau of the words "royal" and "craft," sometimes referred to as the "King’s Craft." The original Roycroft mark (like a ranch brand) contained a single "R" within an orb topped by a cross—but today, it features double Rs, which stand for "Roycroft Renaissance."

The Roycroft Campus, as it's known today, was founded in 1897 by Elbert Hubbard—a former soap entrepreneur-turned-self-publisher and philosopher with a knack for the decorative arts.

He and his (second) wife Alice (Moore) died tragically in 1915 aboard the RMS Lusitania.

But the Roycroft activity didn't cease with their death. Elbert's son, "Bert," took over the leadership position and continued the Roycroft enterprises for another 23 years.

The Hubbard family divested itself of the Roycroft campus in 1938—but their memory is everywhere, thanks in part to a 1970s renaissance of the movement.

A boulder dedicated to Elbert and Alice's memory stands outside the circa 1899 chapel (or "guild hall," as it's not consecrated)—which now at one time housed the East Aurora Museum and East Aurora Town Hall.

On a tour of the campus, next to the chapel you'll find the second print shop, built in 1901. (More on the first print shop, which used to be across the street, in a moment.)

Hubbard used the 24,000-square-foot shop for publishing his own works, often under the pen name "Fra Elbertus." He was kind of a late 19th century/early 20th century version of Thomas Paine—though he was considered an anarchist and was even convicted of circulating "obscene" material through the U.S. Postal Service. The proverb "When life gives you lemons, make lemonade" is based on a piece of Hubbard's writing.

Hubbard's popularity as a writer blew up around the turn of the last century—so much so that his self-publishing endeavor required 23 printing presses on the first floor of his print shop, a typesetting and composing department on the second floor, and a department for collating, folding, binding, mailing on the third floor.

The Roycroft Press reportedly imported more handmade paper than all other American printing industries combined.

Printed matter served as a jumping off point for Roycroft, which expanded into a full-fledged colony of artisans working in different media—including metalsmithing. A second blacksmith shop was built in 1902—out of the same local rock as the chapel and print shop—and, in 1904, was converted into the copper shop.

Copper ultimately became the second-most popular Roycroft output, behind its books, pamphlets, and other printed works. Today, the copper shop is the Roycroft Campus gift store.

Behind the copper shop is the wooden furniture shop, built in 1904—whose top floor burned in 1981. The building still stands—one floor shorter—and is privately owned, housing an antique store.

Handcrafted Roycroft furniture—with its "R" brand carved into the wood—was popular as well, enough to get a distribution deal with the Sears and Roebuck catalogue. But it never reached the volume or the heights of success of, say, Stickley.

The furniture shop also housed the leather shop and bindery, which moved from the print shop when leather goods became their own category (rather than simply as a means of binding books).

Across from the furniture shop is a replica of the circa 1910 power house, which once provided electricity and heat to the rest of the campus through underground pipes. It burned down in 1997 but was rebuilt in 2012, now functioning as the visitors center (which was unfortunately closed for COVID-19 during my tour).

Now, those campus buildings were where artisans learned or honed their crafts—but where some "Roycrofters" got to actually show off their skills was the Roycroft Inn across the street.

Elbert Hubbard had built his "country Gothic" structure to function as the original print shop of The Roycroft Press in 1897. But when the printing demand grew, the Press moved over to the second print shop built in 1901. Around that same time, the Roycroft movement was drawing visitors who needed a place to stay—and the newly-minted Inn began to welcome guests in 1905.

Three separate but adjacent buildings were connected into one by a peristyle porch built by William Roth, Roycroft's head carpenter (and cabinetmaker).

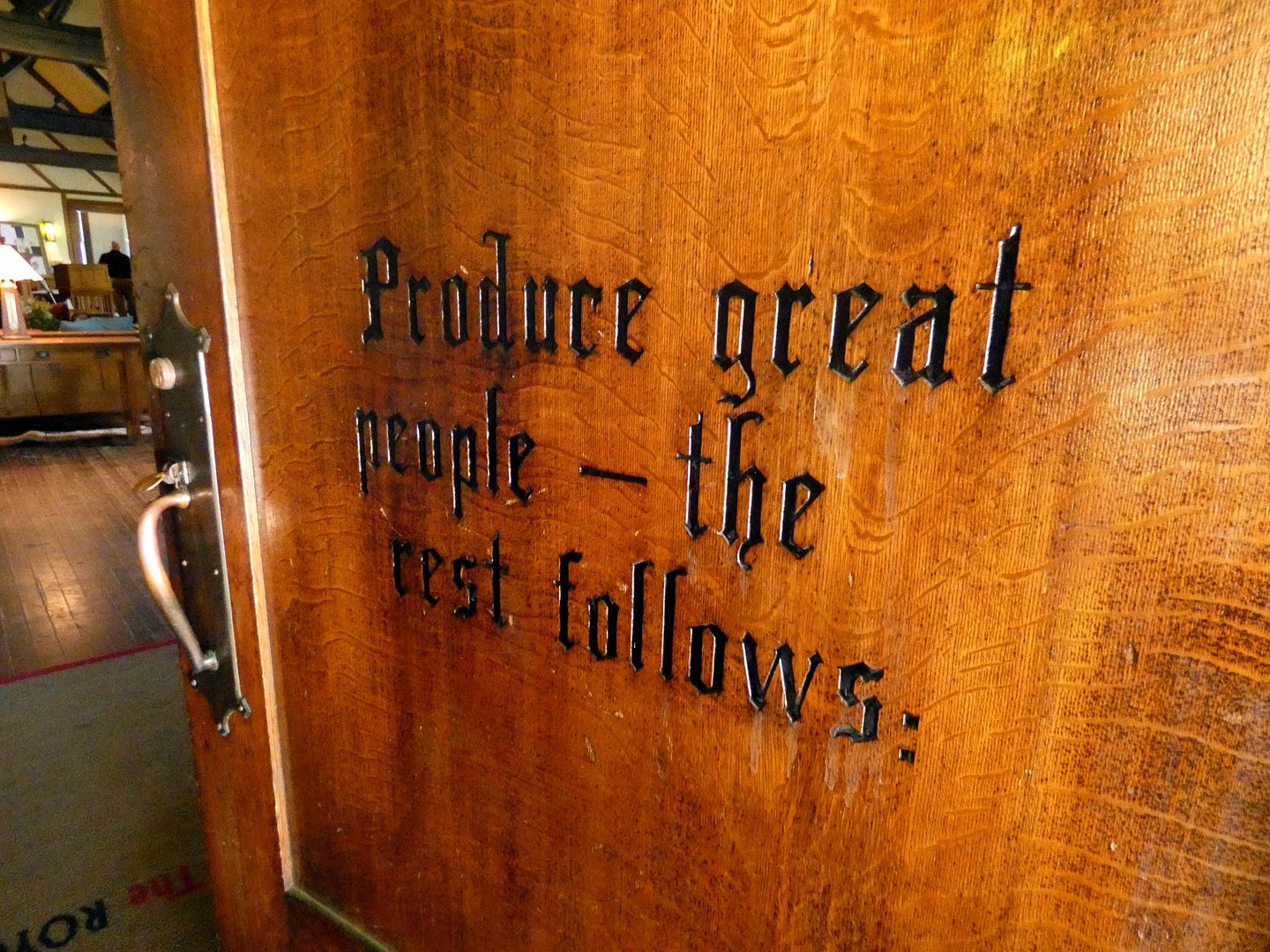

Carved into the wooden front door is a gender-neutralized version of the Walt Whitman quotation, "Produce great men, the rest follows"—and elsewhere, Elbert Hubbard's own aphorisms like "The love you liberate in your work is the love you keep" were meant to inspire his print shop workers.

Hubbard believed in a strong work ethic (as expressed in his popular essay A Message to Garcia and his magazine The Philistine)—but not in being a workaholic. He insisted his staff take their meal breaks—and even had a bell rung on campus at mealtime. In the current dining room, there are wood-carved placards encouraging "self-reliance" and "reciprocity"—and reminding guests to "Fletcherize" (or chew about a million times before swallowing).

Hanging from the truss ceiling in the Roycroft Inn's reception room are the words "service" and "equanimity," the latter of which essentially means "grace under pressure."

In that same room, which was redesigned in 1905 by Elbert's wife Alice with Roycroft furniture craftsman James Cadzow as builder/architect, you'll also find murals painted by Roycrofter Alexis Jean Fournier...

...and lighting fixtures (circa 1908) by Roycrofter Dard Hunter, a graphic designer who apprenticed in stained glass...

...and contributed the Roycroft Inn's leaded glass windows with the "Glasgow rose" design.

After the Hubbards' death in 1915, their daughter-in-law—Bert's wife Alta (Fattey) Hubbard—took charge of the inn and operated it until its sale in 1938.

A stint housing military during WWII closed it to the public for a few years, but the Roycroft Inn managed to reopen to civilian guests and function as a hotel through the 1980s. It underwent a $10 million restoration in 1997—during which time local Western New York-based artists helped restore or recreate some of the pieces of furniture and works of art.

■ ■ ■

The Arts and Crafts Movement was essentially a response to the Industrial Revolution—and tried to pull focus away from machines and back to man and his handiwork.

And Roycroft's success proved not only that there was still a demand for handmade wares—including illuminated manuscripts—but also that it was possible to produce these goods on a larger scale.

At its peak, Roycroft employed over 500 people.

But, in the end, the machines—and robots and computers—seem to have won.

Books have become electronic. Furniture is made from fiberglass or wood composite.

Copper pennies are copper-coated zinc. Leather is pleather.

Even craft beer has become corporatized.

Of course, I grew up in a world that was a result of the Machine Age—and the Information Age. I'm pretty much used to it.

But the ideals of the Roycrofters do seem idyllic, especially the "Roycroft Creed":

A belief in working with the head, hand and heart

and mixing enough play with the work

so that every task is pleasurable

and makes for health and happiness.

Maybe we can look forward to another backlash, as our world becomes more computerized and intelligence becomes increasingly artificial.

I'd like to learn how to smith some copper.

The Chapel has not been the Town Hall or Museum for several years.

ReplyDeleteChapel, as used by Hubbard, meant a place of printers as defined in the dictionary. Was not meant as a church building.

ReplyDeleteSamuel Guard, once associated with Roycroft, was a publisher in Spencer, Owen County, Indiana, for a time. I have written a feature article about Mr. Guard, who was quite a multifaceted man. I am not anonymous - Dixie Kline Richardson, Bloomington IN

ReplyDelete