[Last updated 4/6/24 7:38 PM PT—Added two photos of the Avenue 60 exit.]

Why do I do this to myself.

That's what I was thinking as I sat waiting for the Gold Line (a.k.a. "A Line") Metro train at the Heritage Square station, numbered bib safety-clipped to my tank top.

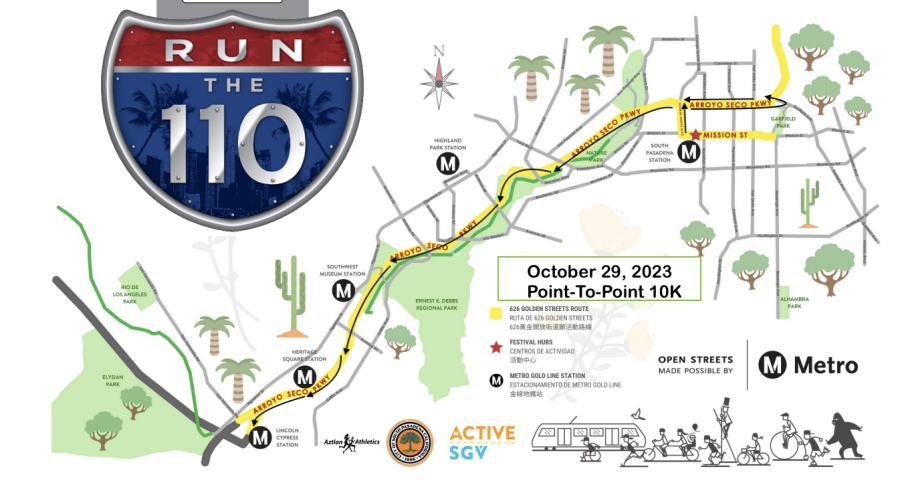

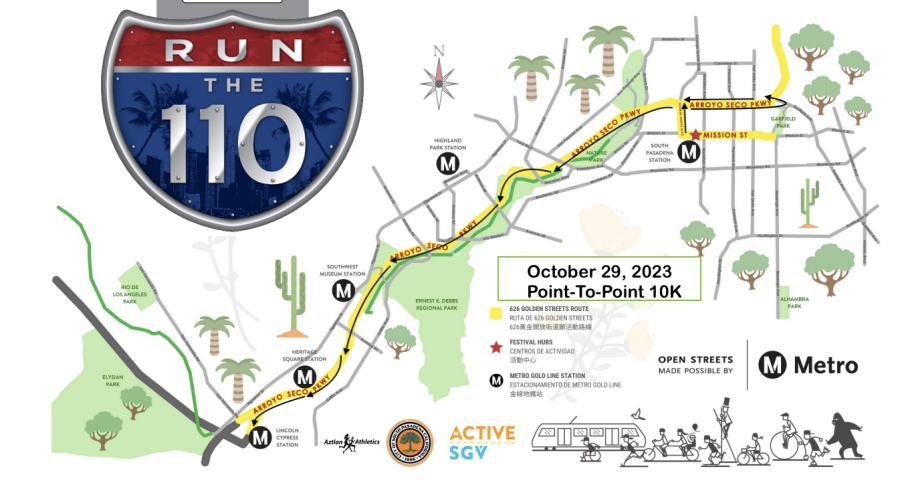

I'd parked just three stops away from the starting point of the "Run the 110" race I'd signed up for—a 10K, though I'd never done a 10K before, and although I had no intention of actually running it.

But it was a special way of experiencing the 110 Freeway when it was closed to traffic—and for the first time in 20 years.

Sure, I could've just walked on the 110 at my leisure, not gotten up at 5 a.m. and not hightailed it to South Pasadena for a 7 a.m. starting time. I could've just joined everybody else during the event known as "ArroyoFest," part of the 626 Golden Streets open street event.

But I wanted to be held accountable to do the whole thing. I wanted to make sure I would go at all—knowing my habit of bailing on myself when I haven't gotten enough sleep or when I'm in a flare-up.

And that meant paying good money to get a T-shirt, be assigned a number, and receive a medal for finishing. Even though I wasn't sure if I could finish the whole thing.

A 10K is actually "only" 6.2 miles, a distance I've walked—and even hiked—before in my life, though not in recent years. Even the 5K races I've done before (and the 4 miles I walked for the Navy Bridge Run last year) have been enough of a challenge for me to wonder what happens if I can't make it in time.

But this time around, I knew I had four hours to get to the finish line—and, based on my normal hiking speed for 6 miles, I might only need three.

I was regretting my decision to sign up for the "run" as I crossed the starting line and headed down Orange Grove Avenue—that is, until I stood on the overpass and looked down at the freeway.

I got a little choked up watching the throngs headed down the on-ramp, tightly packed and excited to begin their journey.

And I felt a sense of community, being among the first to step foot on the car-free roadbed—though it's a community I've never felt I belonged in.

I still didn't want to run—I wasn't even tempted by that—but I was so happy to be walking among them, witnessing their historic run.

The race course took us north up the southbound side of the 110 initially...

...through historic underpasses that date back to the opening of the 110 itself back in 1940 (though sections of it were open as early as 1939, making it America's first freeway)...

...all the way to the turnaround point at Fair Oaks in SoPas.

Up until that point, we'd been facing the sunrise, and it felt dark—but now facing south, the light of day began to kiss the palm fronds and bathe the lush landscape in golden morning glow.

No headlights needed.

In the beginning, we "racers" had a portion of the course to ourselves, as we were separated from bicyclists and other "rollers" on the northbound side by a center divider—but quickly enough, we were intermingling with the regular runners, pedestrians, and strollers who'd shown up on their own without registering for the race.

I didn't bother trying to keep pace with anybody else wearing a bib. I was going to make sure I captured all the details I never noticed from the driver's side of my car, and that I might never seen on foot again.

By the first mile marker, I hadn't even double-backed to the point where I'd started yet...

...and I was already feeling the strain.

I was glad to see others taking pause and taking stock. It would be a shame for all the sights to simply go whizzing by.

The signs that normally help guide drivers—and keep them on the winding course of the freeway, also known as the Arroyo Seco Parkway—actually helped propel me forward in my amble.

To the Finish Line

After passing a pedestrian/equestrian undercrossing, this time over a bridge instead of under one, I stopped for a moment to listen to a pianist play—his unamplified tinkling not competing very well with the various bike-mounted boom boxes blasting Top 40 and hip hop.

While walking and looking and thinking, I had a much greater sense of place...

...and of time...

...than I ever do when I'm just speeding along, on my way to or from Pasadena, taking anything but the "pleasure drive" for which this parkway was intended.

Turns out, in some sections, the 110 Freeway just looks like a regular road—and not at all like a highway.

That's part of what makes it feel so dangerous when you're driving it.

When it opened in 1940, it provided an essential connection between the city of Los Angeles and the suburb of Pasadena.

But back then, traffic wasn't like it is now. They had the luxury of constructing a picturesque "parkway," whose undulations require slowing down to a creeping 40 mph. (Actually, it was probably even slower back then, when the maximum speed limit was a mere 45 mph, then considered "high speed"—though it's now a terrifying 55 mph.)

In many of the neighborhoods it cuts through, it's not even elevated—running right alongside residential streets and homes, separated only be curbs and a chainlink fence. (Freeway construction unfortunately created a number of dead ends along the side streets.)

In fact, originally there was only meant to be one "fast lane," really—the passing lane closest to the center median. That's why it's paved, and the other two aren't.

Caution-yellow signs warn, "Watch for Slow Vehicles" because at several of the entrances and exits, there aren't any ramps at all—just some red reflectors (an original feature), a stop sign (perhaps not an original feature), and a Hail Mary prayer that you won't get hit.

As I approached the York Boulevard Bridge, it was easy to see the "park" part of the parkway—with a short stretch of plantings along the center median (originally built to deter head-on collisions) keeping the freeway a little more green than what you'd normally see in LA. (This section of the 110 was also designated an alignment of Route 66 when it opened.)

The York Boulevard (a.k.a. Pasadena Avenue) Bridge predates the parkway—built in 1912 to cross over the "dry creek" of the Arroyo Seco, which meanders mostly alongside today's freeway.

I couldn't resist doing a little "woo" as I was passing through its reinforced concrete tunnel, thinking it would be really fun to ride a bike through there, too.

[Ed: Added 4/6/14] At the Avenue 60 exit, you can find some of those original red reflectors I mentioned earlier—though I missed them the first time around and had to go back twice later (driving, of course) to finally find them.

The reflectors themselves are broken and non-functional—and the amber-colored flashers that were once there seem to be obliterated—but even just to see some red glass shards left behind was pretty cool.

Another historic bridge along the historic corridor—specifically, in the LA neighborhood of Highland Park—is the Santa Fe Arroyo Seco Railroad Bridge (which currently bears the sign "Arroyo Seco Viaduct"). Soaring 100 feet above the present-day road and anchored on steel supports, it was built in 1896 for Southern California Railway trains to cross the (mostly) dry river, and currently carries the Metro up and over the 110 from Garvanza to South Pasadena.

The 110 Freeway was actually way more historically intact than I expected, with plenty of vintage Portland Cement Concrete exposed and not paved over with asphalt blacktop. I even spotted one of contractor J. E. Haddock's original road stamps, dated May 12, 1940 (a few months before the official full opening on December 30 of that year, just in time for the Rose Parade).

The race organizers had planned a single water stop/rest break area, at the halfway point (around the 3-mile mark).

Although I really needed a rest, I had much more to see along the scenic byway—so, I took a quick swig and kept going.

It was the Sunday before Halloween—another reason I thought I'd been pretty stupid to sign up, given my busy Spooky Season schedule—and the costumes were out in full force.

I swear I saw a Sasquatch ride past me on a bicycle.

By the time I got to the Avenue 43, I'd already considered quitting and taking the Metro the rest of the way multiple times. (The proximity to so many Metro stations made the ArroyoFest route incredily convenient for non-racers who wanted to simply hop on and hop off the 110.)

At the Avenue 35 underpass, I considered just going back to where I'd parked my car, and giving up on the whole thing.

But I'd almost made it—though I was certain that all the other racers had already passed me long ago, and I was the only one lagging behind.

That last quarter-mile was the longest of my life.

The course had been thankfully flat (or even downhill) the whole way—but at the very end, I had one last ramp to climb.

I'd been limping since Mile 4, so it still wasn't a sure thing that I'd actually cross the finish line—until I actually did, in under three hours total and at a pace of a 25-minute mile (not bad, since my normal pace is a 20-minute mile). I didn't finish last overall, either—there were four people who were slower than me, although I was dead last among the females in my age group.

From the finish line, I headed over to the Lincoln Heights Metro station to collect my medal—but there was just one problem. There were no medals. At the time, they didn't know whether they had just run out, or if they'd lost some, or what happened. They wrote down my bib number and told me they'd mail one to me.

I burst into tears and sobbed the whole train ride from Lincoln Heights back to my car. Sure, I hadn't done the race only for the medal. But that medal had been a huge motivator to get me to finish and not tap out early. I felt robbed of my victory—or, at least, some tangible symbol of it.

Because even though I was slow, even though I'd struggled, I still did more than those who never even tried—those who didn't get up as early as I did, hadn't made the commitment I had. And without the medal, it was as though it never happened.

Fortunately, I didn't have to wait for the race organizers to mail me a medal. They'd recovered some medals that had been shockingly stolen, so I was able to go pick mine up just a week later.

By then, my Halloween manicure was over a week old and chipped. But I returned to the end of the race course with my medal to get that photo I wasn't able to pose for on race day.

And hopefully one day I'll forget that feeling of the moment being taken from me.

No comments:

Post a Comment