In 1928, it was about to get a new home, too—its fourth in San Diego, and its most magnificent yet.

There had been just one obstacle to its construction. The Hotel Beacon was standing on the corner lot at 6th and Broadway, which SDSB had purchased in 1924.

So, the old hotel got demolished; the new 13-story bank headquarters got built as the tallest building in San Diego at the time. (It would hold that honor until 1960.)

The funny thing is, though the bank building is still there, it's no longer a financial institution—but a hotel!

It's now the Downtown/Civic Center Marriott Courtyard (and probably the nicest Marriott Courtyard anywhere).

What goes around, comes around, I guess.

Built by William Simpson Construction Company at a cost of approximately $1.4 million, the San Diego Trust and Savings Bank building is one of only three banks ever designed by master architect William Templeton Johnson. Most would probably agree it was his best.

Its "bones" are made of steel reinforced concrete, but what you see on the outside is two stories of buff-colored sandstone quarried from Briar Hall in Ohio (perhaps its first exterior use on the West Coast)...

...perched atop a base of pink granite known as Scotch Rose.

The experience of walking through the bronze revolving door of the main hotel entrance now is meant to be quite similar to when the building functioned as a bank.

The Grand Lobby is largely intact from its former financial function—the circular antique chandeliers still hanging from the hand-painted, coffered plaster ceiling (rising 32 feet in height) and surrounded by 35 marble columns topped with Corinthian capitals. In all, 19 different types of marble were quarried from several Mediterranean countries as well as other sources around the world.

The lobby in particular evokes a medieval atmosphere, as it features all the ornamentation that came into fashion in the Middle Ages—clerestory windows behind iron grilles, grand arches, medallions, and such. Much of those arise out of the Italian Romanesque Revival/Italianate Renaissance Revival architectural style (the The San Diego Union called it "Lombard-Romanesque" at the time of its opening)—less common in commercial buildings like this one and more frequently found in churches.

In addition to the banking services offered to the public (from the basement through the mezzanine levels), the building also housed offices in its upper stories...

...and its original office building entrance is still there, just beyond the massive arches of the elevator lobby, the wall paneling of Italian marble, and the floor of Tennessee marble (from Gray Eagle Quarry).

One of the original bank tables—once positioned near the teller cages for customers to fill out their paperwork and sign checks—has been relocated to the elevator lobby, with others sprinkled throughout the current hotel as well.

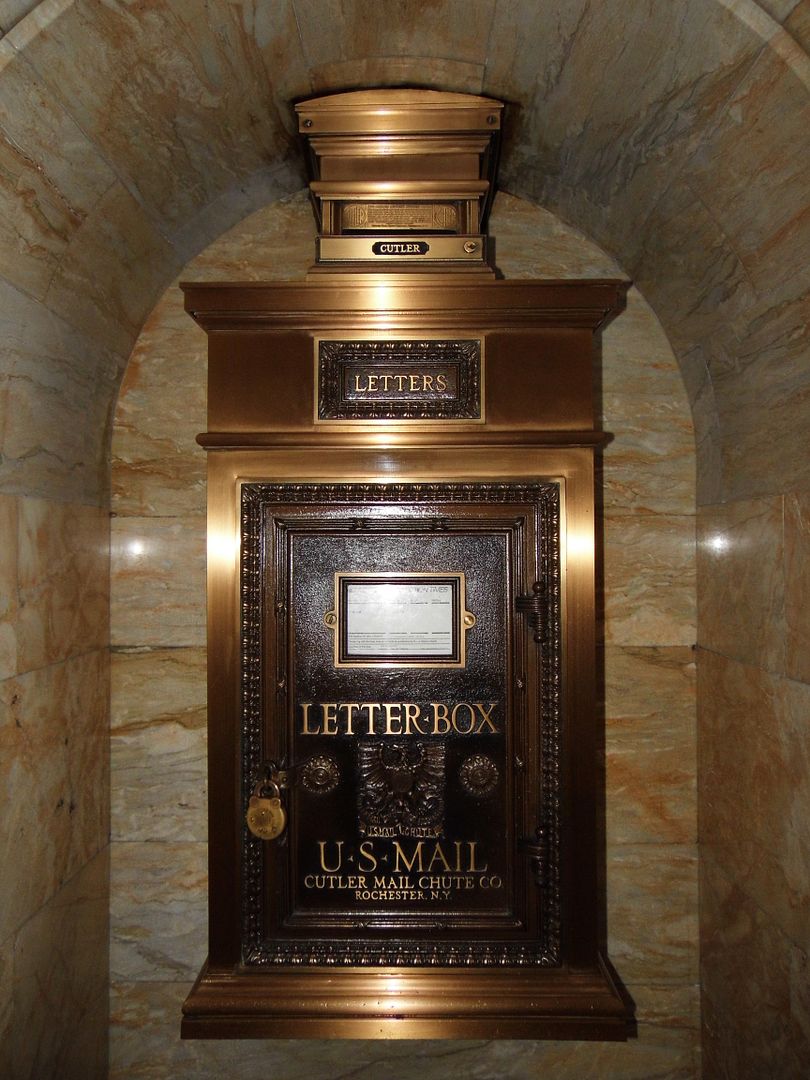

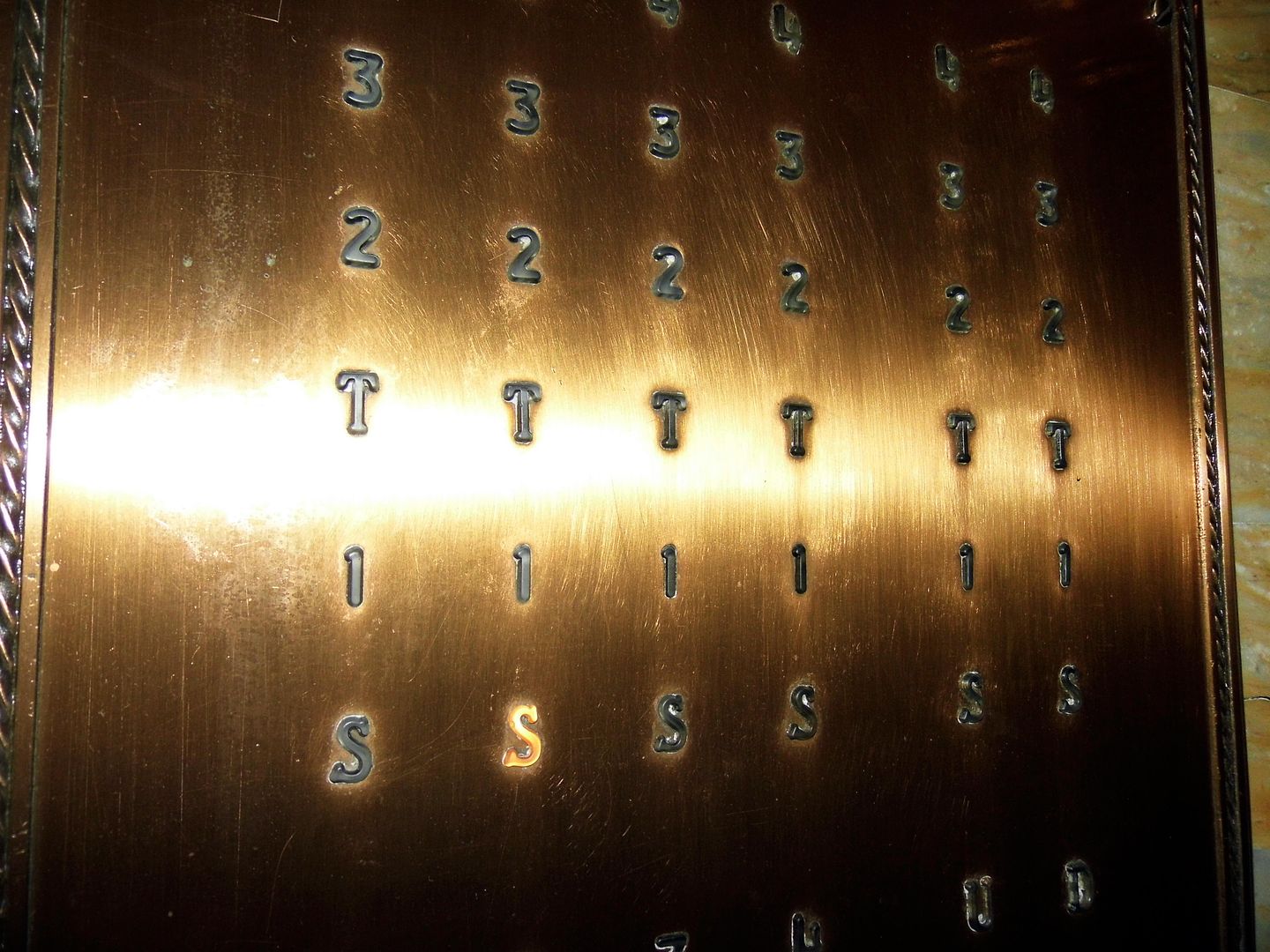

The original mail chute is still mounted in a recessed niche in the elevator lobby—and the post office still picks up the mail every afternoon at 1 p.m.

Behind sculptured bronze doors, hotel guests would find the most technologically advanced, high-speed elevators, which traveled at a maximum rate of 660 feet per minute—more than double most other buildings at the time.

By comparison, the first-ever commercial passenger elevator (in NYC) took a full minute to climb just 40 feet. Today's fastest elevator in the world (China's Rosewood Guangzhou, Guangzhou Chow Tai Fook Finance Centre) travels more than 4100 feet per minute.

The heavy gates leading to the Bond and Investment Service and the one-on-one meeting area still swing—though now they only separate the public from the snacks for sale and a billiard table surrounded by framed, historic photos.

You can still walk down the stairs to the basement in search of the Safe Deposit Department...

...but when you walk through the painted metal vault gates...

...which are no longer locked...

...you'll find the Safe Deposit Room...

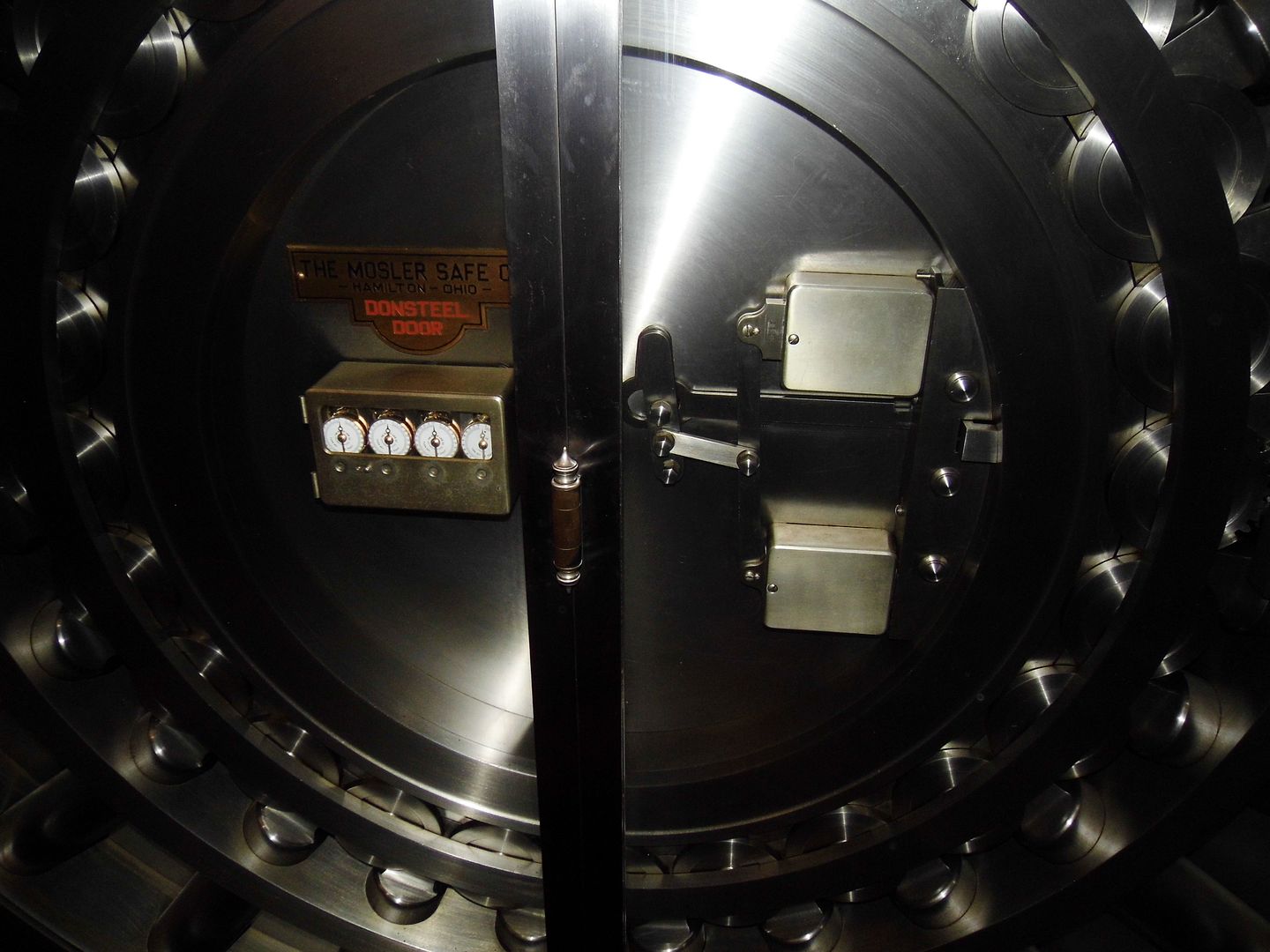

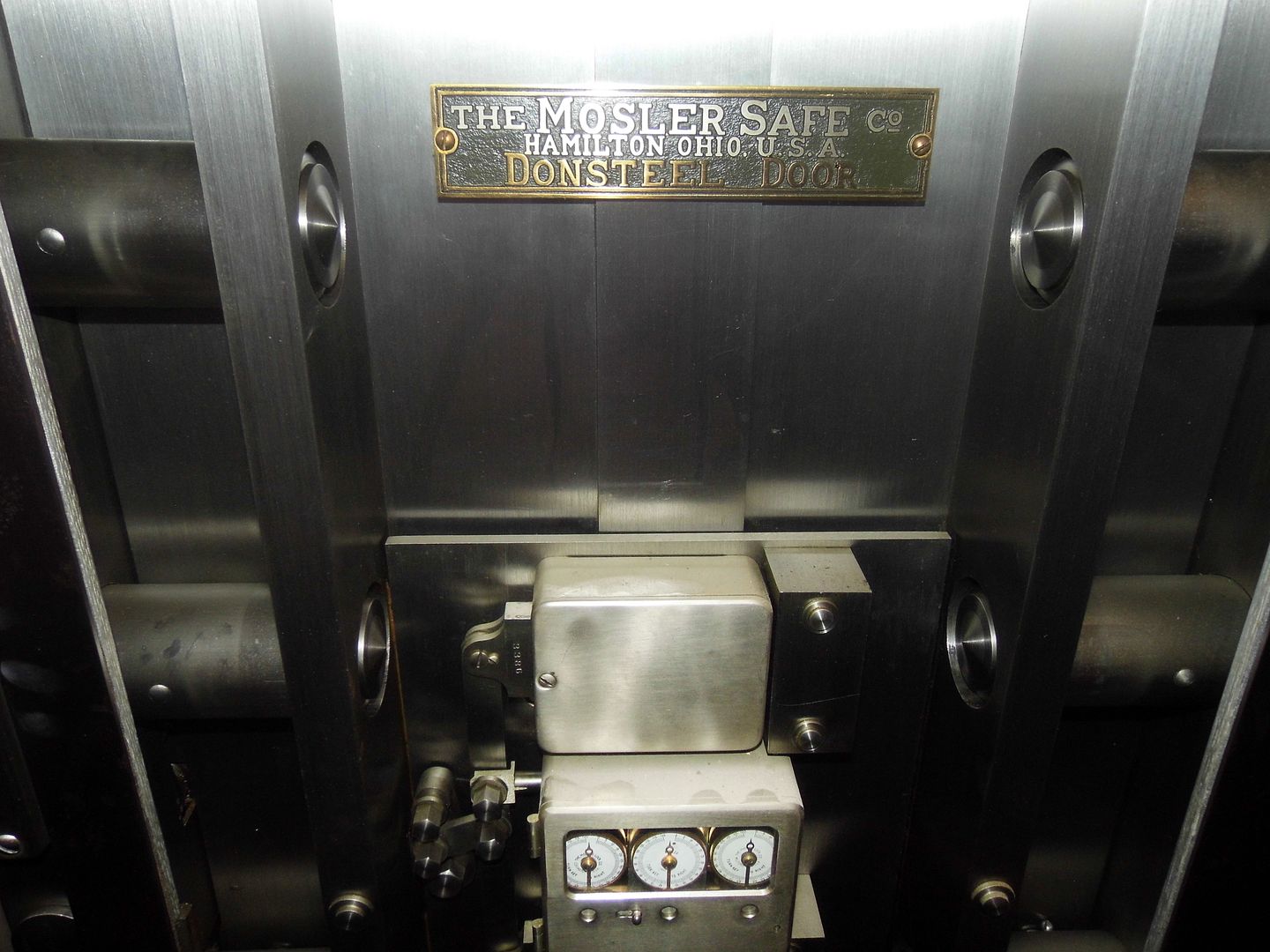

... its original 47,000 lb, stainless steel door (manufactured by the Mosler Safe Company of Ohio, which also provided secure storage for Fort Knox) permanently in the "open" position.

Inside, the safe deposit boxes are empty, but you can still pull them out like the drawers of a cabinet of curiosities, hoping to find something secret, special, or valuable inside.

Although the bank catered to customers of all economic status (including children, who could open an account with a starting deposit of 10 cents), the safe deposit boxes attracted some pretty big-ticket valuables that shouldn't be flashed around out in the open.

Their respective owners would be ushered into tiny offices outfitted with telephones to do their business in private. The three booths are still there—but the old style phones are now push-button, and lifting the receiver directs you to the front desk.

The bank theme continues in the Vault Meeting Room...

...though the "Donsteel" security doors on display are just for show.

San Diego Trust and Savings Bank managed to stay a family business—run by descendants of the bank's co-founder and first president Joseph Weller Sefton, Sr.—until 1994, when the Sefton family decided to get out of banking and sold all 53 branches to the LA-based First Interstate Bank, which was later acquired by Wells Fargo. In 1996, Wells Fargo unloaded several of its San Diego properties and closed up shop on SDTSB.

In its heyday, the bank owned the entire building and occupied most of it—with the exception of the 7th floor's FBI offices and holding cells! (Note how the elevator eliminates the 13th floor, which was rechristened the 14th floor.)

A shooting gallery (for lady tellers to practice their aim in case of a bank robbery) shared the top floor with architect William Templeton Johnson, who occupied a 1,000-square-foot office until 1954. The space is now used as the hotel's Presidential Suite, its master bedroom located in Johnson's former library (decorated with the same kind of hand-painted ceiling as in the Grand Lobby).

Exit onto the patio outside the Presidential Suite, and the view reveals yet another level, above the 14th floor.

It's the copper-domed cupola, a.k.a. the "Lantern," which housed San Diego's first aviation beacon—243 feet above where the Hotel Beacon once stood. This was a really biug deal for San Diego, which had become known as "The Air Capital of the West" in World War I.

Appropriately, the "Father of San Diego Aviation" Major T.C. Macaulay dedicated the beacon, and pioneering aviator Eddie Stinson first switched it on. Visible for more than 25 miles, it revolved from dusk till dawn to guide aviators and navigators trying aim their planes toward the airport—but only during its first five years.

They'd also light the beacon when a ship was coming into the Port of San Diego—not only to help it avoid getting wrecked but to also notify local laborers that jobs were opening up.

Today, the cupola still provides one of the best panoramic views of Downtown San Diego—certainly the best I've seen. Unfortunately, you can't just go up there on your own.

But ask a bellman to give you a tour, and he'll gladly oblige.

When the new San Diego Trust and Savings Bank building opened in 1928, it was the year before the stock market crash that kicked off the Great Depression. But the bank was steadfast.

The bank's second president, M.T. Gilmore, assured its customers that "the present situation is not nearly so perturbing as a more restricted view might suggest"—recalling that in the nearly 40 years since its founding, they'd already experienced five periods of "panic," two wars, and mixed periods of revival and recession.

"This, too, will pass" were the words that continued to carry San Diego Trust and Savings Bank through the next 66 years until the later generation decided to throw in the towel.

Fortunately, the doors on the bank didn't close forever—because it reopened as a hotel in 1999, preserving and reusing a large majority of original elements for the building's new purpose.

Related Posts:

Breathing New Life Into the Eyesores of Downtown LA

No comments:

Post a Comment