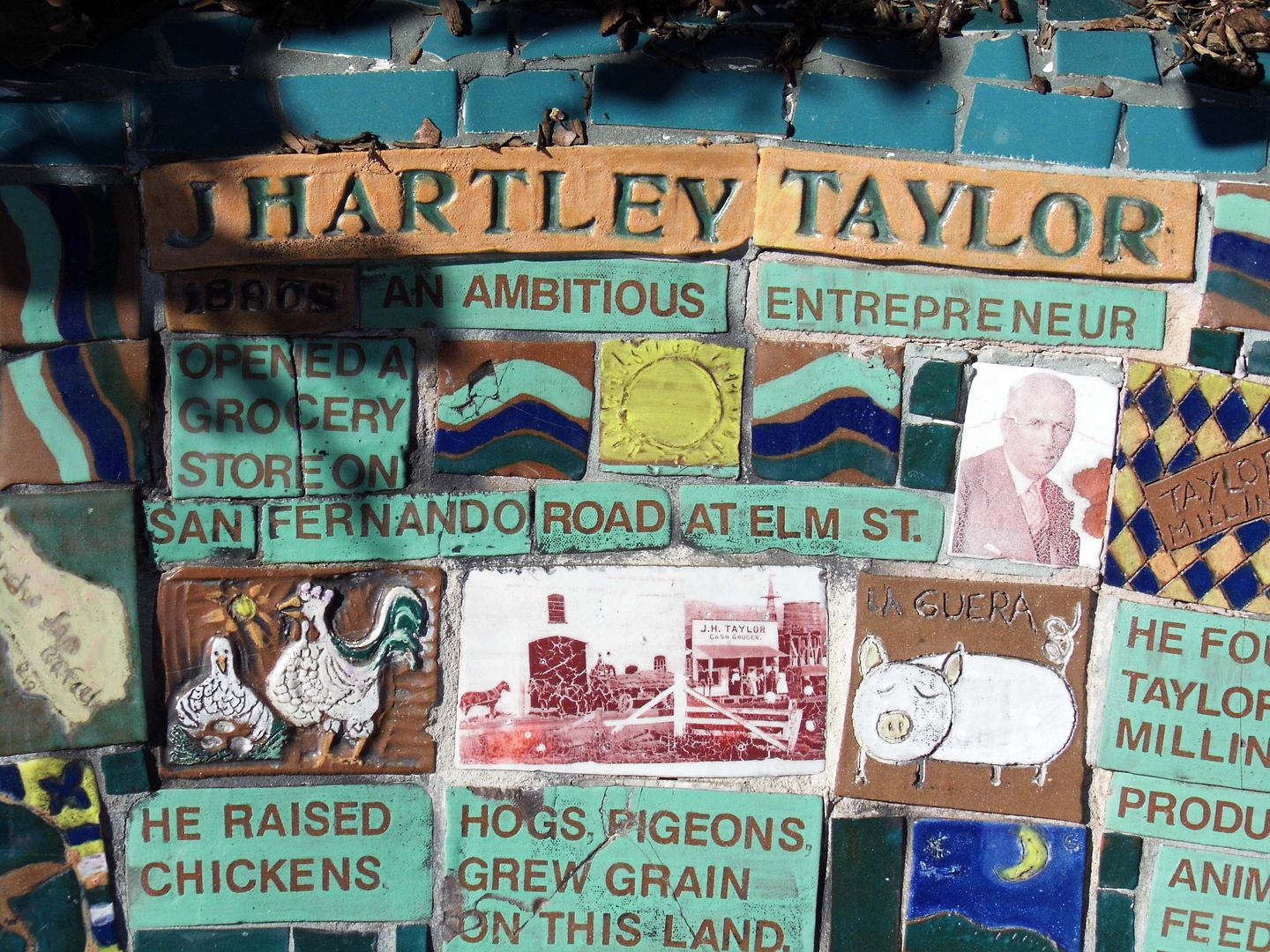

He eventually expanded his hog farm and little grocery into a full-on feed mill and grain storage facility—right where Southern Pacific (later Union Pacific Railroad) had laid down some spur tracks.

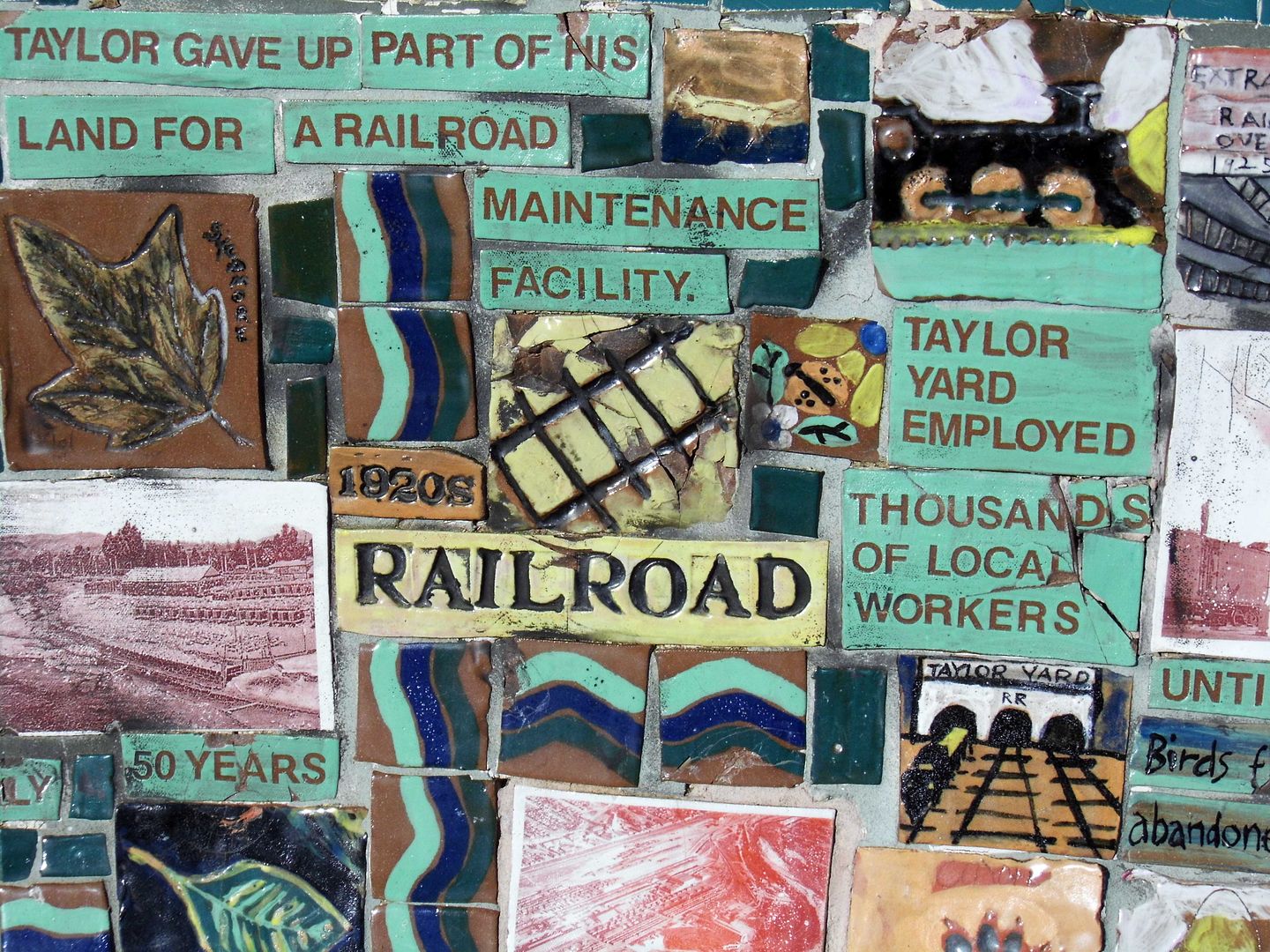

Despite becoming the largest commercial feed supplier on the West Coast at the time, Taylor Milling Corporation's site got taken over by the rail company in 1911—to be used for a railyard, freight-switching facility, storage space and maintenance and repair facility.

Southern Pacific named their new hub Taylor Yard in honor of the grain merchant and continued to build it out into the mid-1920s.

Although about 5,000 employees worked at Taylor Yard at its peak in the 1950s, industrial use of the site declined starting in the 1960s. It really took a hit from the 1973 opening of the computerized and automated West Colton switchyard outside the city of San Bernardino.

Switching operations ceased in 1985, and the remaining storage and maintenance activities ceased in 2006.

Today, alongside those same train tracks is the first parcel of the former 247-acre Taylor Yard (which once had over 2 miles of river frontage) to be subdivided into parkland—Rio de Los Angeles State Park.

Established in 2007 and sandwiched between three densely populated communities adjacent to the river—Elysian Valley, Glassell Park, and Cypress Park, comprised of both industrial and residential areas—it reuses a couple of the old Taylor Yard buildings for park facilities.

A well maintained, unpaved loop winds through the park, past sports fields, playgrounds...

...and a community-created bench that tells the diverse history of the parkland in mosaic tile.

The hogs have been replaced by wildlife, like jackrabbits and plenty of birds...

...and where grain was once stored and sold, native plants now grow.

It's become part of the Los Angeles River Revitalization plan to restore 11 miles of the L.A. River between Griffith Park and Downtown Los Angeles—a plan that also includes another (future) park, an 18-acre post-industrial lot that was also subdivided out of Taylor Yard.

The Bowtie Project (La Parcela Pajarita) is, fitting to its name, shaped like a bowtie (that is, pinched in the middle) and is also along the east bank of the L.A. River—but unlike Rio de los Angeles, it hasn't undergone any infrastructural improvements (though although an asphalt access road leftover from the Taylor Yard days does run the 3/4-mile length of the site).

There may be no restroom, running water, lights, or electricity—but California State Parks, which owns the Bowtie, has partnered with the non-profit community arts organization Clockshop to activate artist projects, performances, and events at this little-known park.

Since 2014, Clockshop has helped interpret the Bowtie Project as an urban space on the cusp of change—with sculptures being placed and events taking place right alongside the piles of rubble and rebar that remain scattered as reminders of the parcel's former use.

I'm glad I got to see it while I could in this state of limbo—with its LADWP power transmission towers, graffitied foundations, and other relics, still intact.

After all, they might not survive a future park overhaul.

Southern Pacific built the roundhouse/turntable, the remains of which are now located at the park's southern tip, in 1931 to service its freight trains.

Situated above the river's natural flood plain, and somewhat protected by Southern Pacific's levee at the river bank, the Taylor Yard operations were spared from the devastation of the 1938 flooding that wiped out a lot of other businesses and residences erected at riverside.

Now, besides the tagged concrete, invasive fountain grass intermingles with native California buckwheat, mulefat, and yerba santa. In the river channel, invasive giant reeds are trying to crowd out the native willows.

There may be some invisible traces of Taylor Yard at the Bowtie, too—maybe arsenic, lead, or anything else that might vaporize into visitors' lungs (e.g. tetrachloroethene/PCE and trichloroethene/TCE, both used at the roundhouse). If necessary, future soil remediation will be funded by the sewer lines that run way below the surface of the park.

The Bowtie Project—formerly known as the Bowtie Parcel—is one half of the Taylor Yard's subdivided Parcel G, designated Parcel G-1. The other half, G-2, lies inaccessible on the other side of some concrete barriers and a chainlink fence.

You can get a little close to the G-2 parcel by climbing down the steep concrete walls of the channelized river. G-2 is the last undeveloped remnant of Taylor Yard, purchased by the City of L.A. in early 2017 for $60 million.

It's slated to open as the 42-acre Taylor Yard River Park in the year 2028—envisioned to be the "crown jewel" of the revitalized river. A pedestrian bridge connecting Taylor Yard with the west bank has been in the works for a long time, so maybe that'll come around the same time?

Honestly, I can't complain. A lot has changed with the Los Angeles River since I moved here 9 years ago. A lot more people know we actually have a river.

Now we're just working more on getting access to it.

For more history on Taylor Yard, view the Historic Resources Survey Report here [opens in new window].

Related Posts:

Photo Essay: An Abandoned Streetcar Route Now Connects Both Sides of the LA River