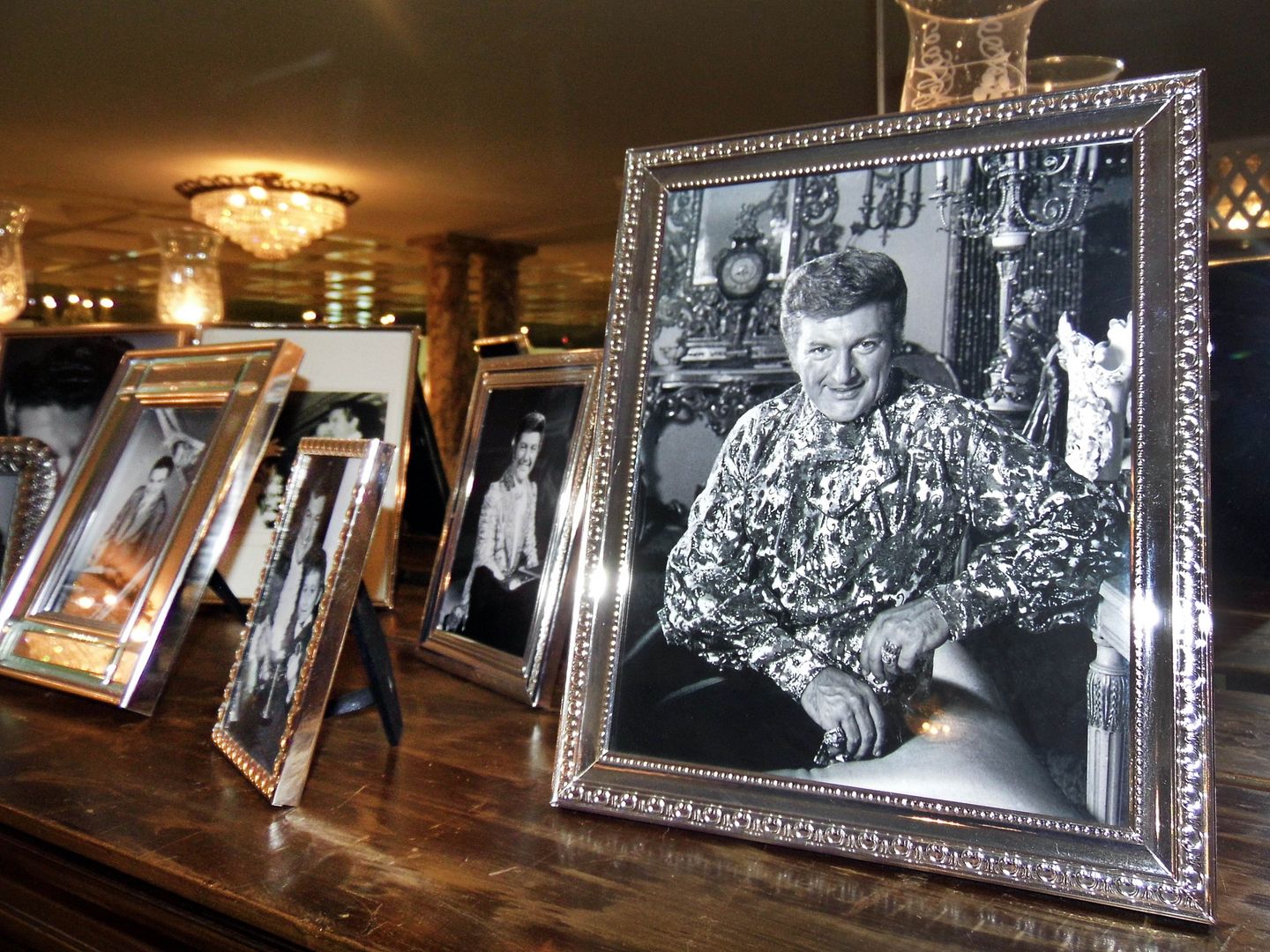

"Mr. Showmanship" may have passed away 32 years ago, but his memory is still very much alive—at least in Las Vegas.

Liberace had made Vegas his home for decades—even putting his mother up in a condo in Beverly Green—but most people associate him with the "Liberace Mansion" on Shirley Street in Paradise, where he lived part-time from 1974 until his death in 1987 (though he was in Palm Springs at the time and also owned properties in Lake Tahoe, Lake Arrowhead, LA, Manhattan, and Malibu).

The entertainer had actually combined two homes to create the largest residence on the block—or probably in the whole neighborhood—the whole thing blinding in sun-bleached white stucco.

The exterior looks pretty modest now for a mansion—but when it went into foreclosure in 2010, it was in shambles. That's how its current owner managed to buy it for $500,000 in 2013.

In 2016—after a huge turnaround—the 14,393-square-foot residence (located in a pretty modest neighborhood) became first residential property to become a county Historic Landmark in Clark County, Nevada.

The European influences and imported goods abound, starting at the sidewalk with an Italian wrought-iron gate that's a century old...

...and hand-carved wooden front doors that were salvaged from a former governor's mansion (in, I believe, California—though some reports claim New York State), which have since been painted black and gold.

The lavish estate exemplifies Liberace's famous motto—"Too Much of a Good Thing Is Wonderful"—though most of the furnishings are appropriate to the star's taste but not original.

Of course, Liberace's style was known well from his elaborate stage performances, media appearances, and photo shoots.

He was an "open book" when it came to his homes, often inviting the cameras in (as well as many of his celebrity friends).

And when you tour the now-restored Liberace Mansion, you can turn any corner and see Liberace's name screaming out at you.

Many of the walls are mirrored floor to ceiling, some etched with designs in the style of Aubrey Beardsley drawings.

Others are etched with Liberace's name, signature, piano, or candelabra...

...as is the discoball-decorated bar that Liberace had installed.

The mansion's current owner lives in Liberace's former walk-in closet, partially in order to preserve the original master bedroom whose ceiling was painted like that of the Sistene Chapel.

A mirrored hall that mimics Louis XIV's Palace of Versailles—flanked by eight marble pillars imported from Greece—leads to the marble-floored master bath.

Fans recognize the "marble courtyard" with its sunken marble tub from a campy prerecorded video intro to Liberace's concerts, in which he reaches out from a bubble bath to tickle the ivories on an adjacent piano.

His 14-karat gold-plated swan fixtures still dispense water into the whirlpool bath, which reportedly cost Liberace $350,000.

Head upstairs by climbing a gilded spiral staircase that was reportedly hand-sculpted in Italy and shipped in one piece from Paris.

Did it really come from a Parisian can-can bar? I haven't been able to find a primary source for that story.

But we do know that Liberace did hold one of three residential gaming licenses in Vegas—along with Howard Hughes and Frank Sinatra. Hence the slot machines.

Out of all these opulent living areas, it's said that Liberace's favorite was the atrium on the upper floor, with its Tangier-inspired design and Moroccan copper tile. That's where he'd relax after playing one of his Vegas shows.

With as much that's been saved of Liberace's, there's also much that's been lost—and not just the piano key-tiled pool that's now covered by a banquet room.

In October 2010, the Liberace Museum—just a mile down Tropicana Avenue from the mansion—closed after 31 years. With the closure of Liberace's adjacent restaurant Tivoli Gardens, all that's left in the shopping plaza he once owned is a larger-than-life mosaic tile portrait of him.

Fortunately, some of the Liberace-owned memorabilia—including pianos and cars—have relocated to "Liberace's Garage" at the Hollywood Cars Museum...

...like his custom Bradley GT sports car (finished in gold metalflake) and a rhinestone-encrusted Rolls.

Many of the contents of the Vegas museum are now housed at the "Thriller Villa," a one-time vacation rental home of Michael Jackson that's become a tourist attraction.

Liberace had wanted to open museums in Palm Springs and the Midwest where he was born and grew up, but those never came to fruition.

And so much of what Liberace had collected over the years was auctioned off right after his passing—enough stuff to fill the LA Coliseum.

A Palm Springs auction was held in 2016 during Modernism Week—a sign, I suppose, that the Palm Springs Liberace museum will never come to fruition.

One of Liberace's favorite songs to perform was "The Impossible Dream." I guess even if your dream is impossible, that doesn't mean you shouldn't dream it.

Related Posts:

Photo Essay: A Bit of Hollywood in Vegas

Photo Essay: At Home With Mr. Las Vegas

Photo Essay: The Other Elvis of Palm Springs, The Elvis of My Childhood